🦋🤖 Robo-Spun by IBF 🦋🤖

🤖🧠 Saikbilim Evirileri 🤖🧠

Dated December 1957–January 1958, published in La psychanalyse, 1958, no. 4, “Les Psychoses,” pp. 1–50.

Hoc quod triginta tres per annos

in ipso loco studui, et Sanctae

Annae Gento loci, et dilectae

juventuti, quae eo me sectata est,

diligenter dedico.

[This, which for thirty-three years

I studied in this very place, and to Saint

Anne of Ghent, the place itself, and to the beloved

youth who followed me there,

I dedicate with care.]

I. Toward Freud.

1. Half a century of Freudianism applied to psychosis still leaves its problem to be rethought—in other words, back to the statu quo ante.

One could say that before Freud, the discussion never detached itself from a theoretical background that presented itself as psychology and was merely a “secularized” residue of what we will call the long metaphysical stew of science in the School (with a capital S, which our reverence owes it).

Now, if our science, concerning physis, in its ever purer mathematization, retains from that stew only such a faint trace that one can legitimately wonder whether a substitution of person has not occurred, the same cannot be said regarding antiphysis (that is, the living apparatus assumed capable of taking the measure of the said physis), whose stink of fried brains unmistakably betrays the centuries-old practice, in that very kitchen, of preparing minds.

Thus the theory of abstraction, necessary for accounting for knowledge, became fixed as an abstract theory of the subject’s faculties, which even the most radical sensualist assumptions failed to render more functional regarding subjective effects.

The ever-renewed attempts to correct the results with various counterweights of affect must in fact remain vain, as long as one omits to ask whether it is indeed the same subject that is affected.

2. It is the very question one learns to sidestep once and for all on the benches of school (with a small s): since, even when one admits the alternations of identity in the percipiens, its constitutive function in the unity of the perceptum is not questioned. From then on, the structural diversity of the perceptum only affects the percipiens as a diversity of register—ultimately, a diversity of sensoriums. In principle, this diversity is always surmountable, if the percipiens stands up to the level of reality.

This is why those tasked with responding to the question posed by the existence of the madman could not help but interpose, between the question and themselves, those school benches, which they found on that occasion to be a convenient wall behind which to take shelter.

Indeed, we dare to throw into the same bag, so to speak, all the positions—whether mechanistic or dynamistic in nature, whether genesis is located in the organism or in the psyche, and whether the structure is one of disintegration or conflict—yes, all of them, however ingenious they may be, insofar as, in the name of the manifest fact that a hallucination is a perceptum without an object, these positions content themselves with calling upon the percipiens to account for this perceptum, without anyone realizing that in doing so, a step has been skipped: that of questioning whether the perceptum itself offers an unambiguous meaning to the percipiens now being asked to explain it.

This step should, however, appear legitimate to any unprejudiced examination of verbal hallucination, insofar as it is not reducible, as we will see, either to a particular sensorium, nor above all to a percipiens in the sense that it would confer unity upon it.

Indeed, it is a mistake to consider it auditory by nature, when it is conceivable, at the limit, that it is not so to any degree (for example, in a deaf-mute, or within any non-auditory register of hallucinatory spelling); but above all to consider that the act of hearing is not the same depending on whether it targets the coherence of the verbal chain—namely, its overdetermination at each moment by the after-effect of its sequence, as well as the suspension at each moment of its value in the advent of a meaning always poised for referral—or whether it adjusts, in speech, to sound modulation, for some purpose of acoustic analysis: tonal or phonetic, even of musical power.

These very brief reminders would suffice to highlight the difference between the subjectivities involved in the aiming at the perceptum (and how profoundly it is overlooked in the interrogation of patients and in the nosology of “voices”).

But one could claim to reduce this difference to a level of objectivation within the percipiens.

However, this is not the case. For it is at the level where the subjective “synthesis” confers its full meaning to speech that the subject reveals all the paradoxes of which he is the patient in this singular perception. That these paradoxes already appear when it is the other who utters the speech is made clear enough in the subject by the very possibility of obeying it insofar as it commands his listening and his alertness, for merely entering its audience subjects the individual to a suggestion from which he can only escape by reducing the other to being no more than the spokesperson of a discourse that is not his own, or of an intention that he harbors there in reserve.

But even more striking is the subject’s relation to his own speech, where what matters is rather masked by the purely acoustic fact that one cannot speak without hearing oneself. That one cannot listen to oneself without being divided is no less unexceptional in the behaviors of consciousness. Clinicians have made a better step in discovering motor verbal hallucination through the detection of sketched phonatory movements. But they have not for all that articulated where the crucial point lies, which is that the sensorium is indifferent in the production of a signifying chain:

- this chain imposes itself upon the subject in its dimension as voice;

- it takes on, as such, a reality proportional to time, perfectly observable in experience, which involves its subjective attribution;

- its structure as a signifier is determinative in this attribution which, as a rule, is distributive—that is, to several voices—thus positing the percipiens, supposedly unifying, as equivocal.

3. We will illustrate what has just been stated with a phenomenon taken from one of our clinical presentations from the year 1955–56, the very year of the seminar whose work we are here evoking. Let us say that such a discovery can only be the price of a complete submission, even if it is informed, to the properly subjective positions of the patient—positions that are too often forced, in dialogue, to be reduced to the morbid process, thereby reinforcing the difficulty of penetrating them by a resistance provoked in the subject not without justification.

This concerned in fact one of those shared delusions of two, the type of which we have long illustrated in the mother–daughter couple, in which the feeling of intrusion, developed into a delusion of surveillance, was only the unfolding of the defense proper to an affective binary, open as such to any form of alienation.

It was the daughter who, during our examination, offered as proof of the insults to which both were subjected by their neighbors a fact involving the boyfriend of the neighbor who was supposedly harassing them with her assaults, after they had been compelled to end a once-pleasant intimacy with her. This man, then a party in the situation in an indirect way, and a rather subdued figure in the patient’s allegations, had, according to her, thrown at her as he passed her in the hallway of the building the offensive word: “Sow!”

Whereupon we, little inclined to recognize in this the retaliatory echo of a “Pig!”—too easily extrapolated in the name of a projection that never, in such a case, represents anything but that of the psychiatrist—asked her simply what within herself might have been uttered the moment before. Not without success: for she conceded to us with a smile that she had indeed murmured upon seeing the man those words which, according to her, he had no reason to take offense at: “I’ve just come from the butcher’s…”

Whom were they aimed at? She was quite at a loss to say, giving us every right to assist her in doing so. For their textual meaning, we cannot overlook the fact, among others, that the patient had taken the most sudden leave of her husband and in-laws, thus bringing to an end—an end that has since remained without epilogue—a marriage disapproved of by her mother, on the basis of a conviction she had come to hold, namely that these peasants intended nothing less, in order to rid themselves of this good-for-nothing city girl, than to properly dismember her.

It hardly matters, however, whether or not one must invoke the fantasy of the fragmented body in order to understand how the patient, imprisoned in the dual relation, here again responds to a situation that overwhelms her.

For our current purpose, it suffices that the patient admitted that the phrase was allusive, without being able to show anything other than perplexity in grasping to whom among those present or absent the allusion was directed, for it thus appears that the I, as the subject of the phrase in direct speech, left suspended, in accordance with its so-called shifter function in linguistics¹, the designation of the speaking subject, as long as the allusion—no doubt in its conjuring intention—remained itself oscillating. This uncertainty came to an end, following the pause, with the apposition of the word “sow,” itself too heavy with invective to follow isochronically the oscillation. Thus the discourse came to realize its intention of rejection in the hallucination. At the point where the unspeakable object is rejected into the real, a word is heard, because, coming in the place of that which has no name, it could not follow the subject’s intention without detaching from it through the dash of the reply: opposing its antistrophe of derision to the lament of the strophe, from then on restored to the patient with the index of the I, and joining in its opacity the jaculations of love when, lacking a signifier with which to name the object of its epithalamium, it employs the medium of the crudest imaginary. “I eat you… – Cabbage!” “You swoon… – Rat!”

4. This example is brought forward here only to grasp vividly that the function of derealization is not everything in the symbol. For the fact that its irruption into the real is beyond doubt is sufficiently indicated by its presentation, as commonly happens, in the form of a broken chain².

Here one also touches upon that effect that every signifier, once perceived, has of arousing in the percipiens an assent composed of the awakening of the second’s hidden duplicity through the manifest ambiguity of the first.

Of course, all of this may be considered as mirage effects from the classical perspective of the unifying subject.

It is simply striking that this perspective, when left to itself, offers on hallucination, for instance, only views of such poverty that the work of a madman—as remarkable as President Schreber proves to be in his Memoirs of My Nervous Illness³—can, after having received the warmest reception, even before Freud, from psychiatrists, still be regarded after him as a collection worth proposing for an introduction to the phenomenology of psychosis, and not only for beginners⁴.

It has, for our part, provided the basis for a structural analysis, when in our 1955–1956 seminar on Freudian structures in psychoses, we resumed its examination following Freud’s recommendation.

The relation between the signifier and the subject, which this analysis reveals, can be observed, as seen in this opening, from the very appearance of the phenomena, if, returning from Freud’s experience, one knows the point to which it leads.

But this departure from the phenomenon, if properly pursued, would rediscover this point, as was the case for us when an initial study of paranoia led us, thirty years ago, to the threshold of psychoanalysis.

Nowhere, indeed, is the fallacious conception of a psychic process in the sense of Jaspers—of which the symptom would be only the index—more out of place than in the approach to psychosis, because nowhere is the symptom, if one knows how to read it, more clearly articulated in the structure itself.

This will require us to define this process through the most radical determinants of man’s relation to the signifier.

¹ Roman Jakobson.

² Cf. https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k6248021z/f17.item.zoom

³ D. Paul Schreber, Denkwürdigkeiten eines Nervenkranken, 1903.

⁴ Freud, “Psychoanalytic Notes Upon an Autobiographical Account of a Case of Paranoia (Dementia Paranoides),” 1911.

5. But it is not necessary to go that far to take an interest in the variety under which verbal hallucinations appear in Schreber’s Memoirs, nor to recognize in them differences wholly distinct from those in which they are “classically” categorized, according to their mode of implication in the percipiens (the degree of his “belief”) or in his reality (“auditivation”): rather, the differences pertain to their structure as speech, insofar as this structure is already present in the perceptum.

By considering the text of the hallucinations alone, a distinction immediately emerges for the linguist between phenomena of code and phenomena of message.

To the phenomena of code belong, in this approach, the voices that use the Grundsprache, which we translate as language-of-foundation, and which Schreber describes (p. 13-I⁵) as “a somewhat archaic but always rigorous German particularly notable for its great richness in euphemisms.” Elsewhere (p. 167-XII), he refers with regret “to its authentic form for its traits of noble distinction and simplicity.”

This category of phenomena is specified in neological phrases by their form (new compound words, but with composition here conforming to the rules of the patient’s language) and by their usage. The hallucinations inform the subject of the forms and usages that constitute the neocode: the subject owes to them, for example, first and foremost, the very term Grundsprache as its designation.

It concerns something quite close to those messages that linguists call autonymous, insofar as it is the signifier itself (and not what it signifies) that becomes the object of communication. But this relation—singular but normal—of the message to itself is here doubled by the fact that these messages are said to be supported by beings whose relations they themselves state, in modes that prove to be highly analogous to the connections of the signifier. The term Nervenanhang, which we translate as annexation-of-nerves, and which also comes from these messages, illustrates this observation in that passion and action between these beings are reduced to these annexed or disannexed nerves, but also because these, no less than the divine rays (Gottesstrahlen) to which they are homogeneous, are nothing other than the entification of the words they bear (p. 130-X: what the voices formulate: “Do not forget that the nature of the rays is that they must speak”).

Here we have a relation of the system to its own constitution as signifier, which should be added to the dossier of the question of metalanguage, and which, in our view, demonstrates the inappropriateness of this notion if it aims to define differentiated elements within language.

Let us further note that we are here in the presence of those phenomena that have wrongly been called intuitive, on the grounds that the effect of meaning precedes the development of that meaning. What we are dealing with, in fact, is an effect of the signifier, insofar as its degree of certainty (second degree: the meaning of the meaning) takes on a weight proportional to the enigmatic void that initially appears in the place of meaning itself.

What is amusing in this case is that it is to the very extent that, for the subject, this high tension of the signifier comes to fall—that is, that the hallucinations are reduced to ritornellos, to refrains, whose emptiness is attributed to beings without intelligence or personality, even clearly erased from the register of being—that it is to this same extent, we say, that the voices report the Seelenauffassung, the conception-of-souls (according to the fundamental language), which conception is manifested in a catalogue of types of thoughts not unworthy of a textbook of classical psychology. A catalogue linked, in the voices, to a pedantic intention, which does not prevent the subject from contributing the most pertinent commentary. Let us note that in these commentaries, the source of the terms is always carefully distinguished—for example, when the subject uses the word Instanz (p. note 30-II—cf. notes from 11 and 21-I), he emphasizes in a note: this word is mine.

Thus, he does not fail to recognize the fundamental importance of memory-thoughts (Erinnerungsgedanken) in psychic economy, and he immediately points to their evidence in the poetic and musical use of modulatory repetition.

Our patient, who inimitably describes this “conception of souls” as “the somewhat idealized representation that souls have formed of human life and thought” (p. 164-XII), believes he has “gained from it insights into the essence of the process of thought and feeling in man that many psychologists might envy” (p. 167-XII).

We willingly grant him this, all the more so because, unlike them, these insights—whose reach he appreciates with such humor—he does not imagine to derive from the nature of things, and because, if he believes he should make use of them, it is, as we have just indicated, on the basis of a semantic analysis⁶!

But to return to our thread, let us come to the phenomena we will contrast with the previous ones as message phenomena.

These are interrupted messages, which sustain a relation between the subject and his divine interlocutor, a relation that takes the form of a challenge or a test of endurance.

Indeed, the partner’s voice limits the messages in question to the beginning of a sentence, the complementary meaning of which presents no particular difficulty for the subject—except by being harassing, offensive, most often so inept as to be discouraging. The steadfastness he demonstrates in not failing to reply, even in thwarting the traps set for him, is not the least important aspect of our analysis of the phenomenon.

But we will pause here again on the very text of what one could call the hallucinatory provocation (or better, protasis). Of such a structure, the subject gives us the following examples (p. 217-XVI): 1) Nun will ich mich (Now, I’m going to…) ; 2) Sie sollen nämlich… (You must, for your part…) ; 3) Das will ich mir… (I’m really going to…), to limit ourselves to these—each of which he must complete with its meaningful supplement, for him unquestionable, namely:

To admit that I’m an idiot; 2) For your part, be exposed (word of the fundamental language) as a denier of God and given over to voluptuous libertinage, not to mention the rest; 3) Really think hard.

One may note that the sentence breaks off at the point where the group of words we could call index-terms ends—those that, by their function within the signifier, designate, according to the term used earlier, the shifters, that is, the very terms which, in the code, indicate the subject’s position from within the message itself.

After this, the properly lexical part of the sentence—that is, the part comprising the words the code defines by their usage, whether common code or delusional code—remains elided.

Is one not struck by the predominance of the function of the signifier in these two orders of phenomena, even encouraged to seek what lies at the core of the association they constitute: of a code composed of messages about the code, and of a message reduced to what, in the code, indicates the message?

All this would need to be carefully transcribed onto a graph⁷, where we have this very year attempted to represent the internal connections of the signifier insofar as they structure the subject.

For this is a topology entirely distinct from the one that might be imagined through the requirement of an immediate parallelism between the form of the phenomena and their pathways of conduction within the neuraxis.

But this topology, which follows the line inaugurated by Freud when he undertook, after opening the field of the unconscious with dreams, to describe its dynamics without binding himself to any concern for cortical localization, is precisely what can best prepare the questions one will later pose to the surface of the cortex.

For it is only after the linguistic analysis of the phenomenon of language that one can legitimately establish the relation it constitutes within the subject, and thereby delimit the order of “machines” (in the purely associative sense that this term has in the mathematical theory of networks) capable of realizing this phenomenon.

It is no less remarkable that it was the Freudian experience that led the author of these lines in the direction here presented. Let us now come to what this experience contributes to our question.

II. After Freud.

1. What did Freud bring us here? We introduced the matter by stating that, with regard to the problem of psychosis, this contribution had led to a relapse.

This is immediately perceptible in the simplism of the mechanisms invoked in conceptions that all reduce to this fundamental scheme: how to make the inside pass into the outside? The subject, indeed, may well encompass here an opaque id, yet it is nonetheless as ego—that is to say, quite explicitly expressed in the current psychoanalytic orientation, as that same indestructible percipiens—that it is invoked in the motivation of psychosis. This percipiens has full power over its no less unchanging correlate: reality, and the model for this power is taken from a datum accessible to common experience, namely affective projection.

For current theories recommend themselves by the absolutely uncriticized mode under which this mechanism of projection is put to use. Everything objects to it and yet nothing changes, least of all the clinical evidence that there is nothing in common between affective projection and its so-called delusional effects, between the jealousy of the unfaithful and that of the alcoholic, for example.

That Freud, in his attempt at interpreting the case of President Schreber—which is poorly read when reduced to the rehashings that followed—employs the form of a grammatical deduction to present the switching of the relation to the other in psychosis: namely, the different ways of negating the proposition “I love him,” from which it follows that this negative judgment is structured in two stages: the first, the reversal of the value of the verb: “I hate him,” or inversion of the gender of the agent or of the object: it’s not me, or it’s not him, it’s her (or vice versa); the second, the interversion of subjects: he hates me, it’s her he loves, it’s she who loves me—the logical problems formally implicated in this deduction do not retain anyone’s attention.

Even more, that Freud in this text explicitly discards the mechanism of projection as insufficient to account for the problem, to then enter into a very long, detailed, and subtle development on repression, which nonetheless offers foundations awaiting our problem—let us just say that these foundations continue to stand unviolated above the stirred dust of the psychoanalytic construction site.

2. Freud later brought “On Narcissism: An Introduction.” It was used in the same way, for a suction-pumping, aspirating and repressing at the whim of the theorem’s tenses, of the libido by the percipiens, who thus becomes capable of inflating and deflating a balloon-like reality.

Freud offered the first theory of the mode by which the ego is constituted through the other in the new subjective economy determined by the unconscious: this was responded to by acclaiming in this ego the rediscovery of the good old unfailing percipiens and of the function of synthesis.

How could one be surprised that no other benefit was drawn from it for psychosis than the definitive promotion of the notion of loss of reality?

That is not all. In 1924, Freud wrote a sharp article: “The Loss of Reality in Neurosis and Psychosis,” in which he redirects attention to the fact that the problem is not that of loss of reality, but of the mechanism by which it is replaced. A speech to the deaf, since the problem is resolved; the props are stored inside, and brought out as needed.

In fact, this is the very scheme with which even Mr. Katan, in his studies where he so attentively revisits the stages of psychosis in Schreber, guided by his concern to penetrate the prepsychotic phase, is content, when he reports on the defense against instinctual temptation—against masturbation and homosexuality in this case—to justify the emergence of hallucinatory phantasmagoria, a curtain interposed by the operation of the percipiens between the drive and its real stimulus.

How this simplicity would have relieved us once, had we deemed it sufficient for the problem of literary creation in psychosis!

3. After all, what problem would still stand in the way of psychoanalytic discourse, when the implication of a drive in reality accounts for the regression of their pair? What could weary minds that tolerate being spoken to about regression, without any distinction being made between regression in structure, regression in history, and regression in development (distinctions made by Freud on each occasion as topographical, temporal, or genetic)?

We will refrain from dwelling here on the inventory of confusion. It is worn out for those we train and would not interest the others. We will simply propose for their shared reflection the sense of disorientation produced, in the face of a speculation devoted to going in circles between development and environment, by the mere mention of those traits which are, nevertheless, the framework of the Freudian edifice: namely, the equivalence maintained by Freud of the imaginary function of the phallus in both sexes (long the despair of enthusiasts for “biological” false windows, that is, naturalists), the castration complex found as the normative phase of the subject’s assumption of his own sex, the myth of the murder of the father made necessary by the constitutive presence of the Oedipus complex in every personal history, and, last but not… the splitting effect introduced into love life by the very repetitive instance of the object always to be rediscovered as unique. Must we again recall the fundamentally dissident character of the notion of the drive in Freud, the principled disjunction between the drive, its direction, and its object, and not only its original “perversion,” but its implication in a conceptual systematics, the one Freud marked out from the very first steps of his doctrine, under the title of the sexual theories of childhood?

Is it not evident that we have long since strayed from all that, in an educational naturism whose only remaining principle is the notion of gratification and its counterpart: frustration, nowhere mentioned in Freud?

Undoubtedly, the structures revealed by Freud continue to support not only the plausibility but the operation of the vague dynamisms that contemporary psychoanalysis claims to direct in its flow. A hollowed-out technique would even be more capable of “miracles,”—were it not for the added conformism that reduces its effects to those of a social suggestion and psychological superstition of ambiguous nature.

4. It is even striking that a demand for rigor appears only in individuals whom the course of events keeps, in some way, outside this concert, such as Mrs. Ida Macalpine, who places us in the position of marveling, upon reading her, at encountering a steadfast mind.

Her critique of the cliché that confines itself to the factor of the repression of a homosexual drive—moreover completely undefined—to explain psychosis is masterful. And she demonstrates it convincingly in the very case of Schreber. The supposedly determining homosexuality in paranoid psychosis is, strictly speaking, a symptom articulated within its process.

This process has long been underway by the time the first sign appears in Schreber, in the form of one of those hypnopompic ideas, which in their fragility present to us sorts of tomographies of the ego—an idea whose imaginary function is sufficiently indicated by its form: that it would be beautiful to be a woman undergoing copulation.

Mrs. Ida Macalpine, in order to rightly open a critique there, nonetheless comes to overlook that Freud, if he places such emphasis on the homosexual question, does so first to demonstrate that it conditions the idea of grandeur in the delusion, but more essentially to denounce the mode of otherness by which the subject’s metamorphosis occurs—in other words, the place where his delusional “transferences” succeed one another. She would have done better to trust the reason why Freud, here again, insists on referring to the Oedipus complex, which she does not accept.

This difficulty would have led her to discoveries that would surely have enlightened us, for much remains to be said about the function of what is called the inverted Oedipus. Mrs. Macalpine prefers to reject all recourse to the Oedipus here, in order to substitute it with a procreation fantasy, observed in children of both sexes, in the form of pregnancy fantasies, which she moreover considers to be linked to the structure of hypochondria⁸.

This fantasy is indeed essential, and I will even note here that the first case in which I obtained this fantasy in a man, it was through a path that marked a turning point in my career, and it was neither a hypochondriac nor a hysteric.

This fantasy, she even subtly—mirabile in these times—feels the need to link to a symbolic structure. But in seeking to find one outside of the Oedipus, she resorts to ethnographic references whose assimilation in her writing is difficult to assess. It concerns the “heliolithic” theme, which one of the most prominent proponents of the English diffusionist school has supported. We recognize the value of these theories, but they in no way appear to support the idea that Mrs. Macalpine seeks to convey of an asexual procreation as a “primitive” conception⁹.

Mrs. Macalpine’s error lies elsewhere, namely in the fact that she arrives at the result most opposed to what she seeks.

By isolating a fantasy within a dynamic she qualifies as intrapsychic, through a perspective she opens on the notion of transference, she ends up designating, in the psychotic’s uncertainty regarding their own sex, the sensitive point where the analyst’s intervention must strike, contrasting the beneficial effects of this intervention with the catastrophic effect—constantly observed, indeed, in psychotics—of any suggestion in the direction of recognizing a latent homosexuality.

Yet uncertainty regarding one’s own sex is precisely a banal trait in hysteria, whose encroachments in diagnosis Mrs. Macalpine herself denounces.

This is because no imaginary formation is specific¹⁰, none is determining either in the structure or in the dynamics of a process. And that is why one condemns oneself to miss both when, hoping to grasp them more closely, one chooses to disregard the symbolic articulation that Freud discovered at the same time as the unconscious, and which is indeed consubstantial with it: it is the necessity of this articulation that he signifies to us in his methodical reference to the Oedipus.

5. How can Mrs. Macalpine be blamed for the harm of this misrecognition, since, for lack of having been dispelled, it has continued to grow within psychoanalysis?

This is why, on the one hand, psychoanalysts are left with no other recourse, to define the minimal cleavage that must be required between neurosis and psychosis, than to rely on the ego’s responsibility in relation to reality: what we call leaving the problem of psychosis at the statu quo ante.

And yet a point was designated quite precisely as the bridge at the border between the two domains.

They even made it the most inflated matter with regard to the question of transference in psychosis. It would be uncharitable to compile here everything that has been said on this subject. Let us see in it simply the opportunity to pay tribute to the mind of Mrs. Ida Macalpine, when she sums up a position fully consistent with the spirit that presently unfolds in psychoanalysis in these terms: in short, psychoanalysts claim to be able to cure psychosis in all cases where it is not a psychosis¹¹.

It was on this point that Midas, one day legislating on the indications for psychoanalysis, expressed himself as follows: “It is clear that psychoanalysis is only possible with a subject for whom there is an Other!” And Midas crossed the bridge back and forth, taking it for a vacant lot. How could it have been otherwise, since he did not know that the river was there?

The term Other, hitherto unheard-of by the psychoanalytic people, had no other meaning for him than the murmur of reeds.

III. With Freud.

1. It is rather striking that a dimension that makes itself felt as that of Something-Other in so many experiences that men live through—not at all without thinking about them, rather while thinking about them, but without thinking that they are thinking, and like Telemachus thinking about expense—has never been thought through to the point of being congruently stated by those whom the idea of thought assures they are thinking.

Desire, boredom, confinement, revolt, prayer, wakefulness (I would like us to pause on this last one, since Freud expressly refers to it in the midst of his Schreber by evoking a passage from Nietzsche’s Zarathustra¹²), and finally panic are there to bear witness to the dimension of that Elsewhere, and to call our attention to it—not, I say, as mere states of mind that the think-without-laughing can put back in their place, but far more significantly, as permanent principles of collective organizations, outside of which it does not seem that human life can be sustained for long.

No doubt it is not impossible that the think-about-thinking that is the most thinkable, thinking itself to be that Something-Other, may always have poorly tolerated such a potential competitor.

But this aversion becomes entirely clear once the conceptual conjunction is made—one that no one had yet conceived—between that Elsewhere and the place, present to all and closed to each, where Freud discovered that without one thinking about it, and thus without anyone being able to think they think about it better than anyone else, it thinks. It thinks rather badly, but it thinks vigorously: for it is in these terms that he announces the unconscious to us—thoughts which, even if their laws are not exactly the same as those of our noble or vulgar everyday thoughts, are perfectly articulated.

There is therefore no longer any way to reduce that Elsewhere to the imaginary form of a nostalgia, a Paradise lost or yet to come; what one finds there is the paradise of childish loves, where—Baudelaire, by God!—plenty of colorful things go on.

Besides, if any doubt remained, Freud named the place of the unconscious with a term that had struck him in Fechner (who is not at all, in his experimentalism, the realist suggested to us by our textbooks): ein anderes Schauspiel, another scene; he repeats it twenty times in his inaugural works.

This sprinkling of fresh water having, we hope, revived the spirits, let us now come to the scientific formulation of the subject’s relation to this Other.

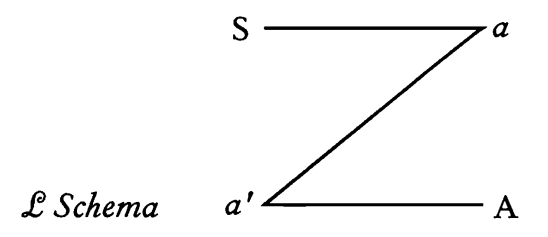

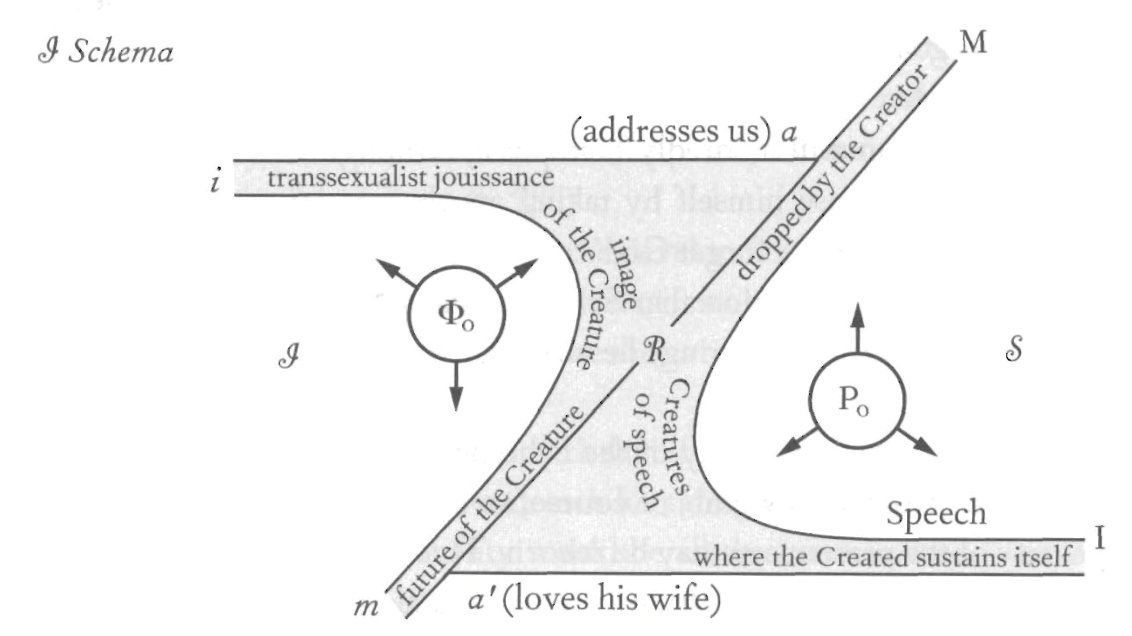

2. We will apply, “to fix ideas” and souls here in distress, we will apply the said relation on the schema L already introduced and here simplified:

which signifies that the condition of the subject S (neurosis or psychosis) depends on what takes place in the Other A. What takes place there is articulated as a discourse (the unconscious is the discourse of the Other), whose syntax Freud first sought to define in those fragments that, in privileged moments—dreams, slips of the tongue, witticisms—reach us from it.

How could the subject be concerned with this discourse if he were not a participant? He is, in fact, drawn to it from the four corners of the schema: namely S, his ineffable and foolish existence; a, his objects; a’, his ego, that is, what reflects of his form in his objects; and A, the place from which the question of his existence may be posed to him.

For it is a truth of experience in analysis that the subject is confronted with the question of his existence—not in the form of the anxiety it generates at the level of the ego, which is only one element of its procession—but as an articulated question: “What am I doing here?”, concerning his sex and his contingency in being, namely that he is man or woman on the one hand, and on the other hand that he might not be at all, both of which combine their mystery and knot it in the symbols of procreation and death. That the question of his existence saturates the subject, supports him, invades him, even tears him apart from all sides, this is what the tensions, the suspensions, the fantasies that the analyst encounters bear witness to; and it must be said that they do so as elements of the particular discourse in which this question is articulated in the Other. For it is because these phenomena are ordered in the figures of this discourse that they have the fixity of symptoms, that they are legible and resolve themselves when they are deciphered.

3. One must therefore insist that this question does not present itself in the unconscious as ineffable, that this question there is a putting-into-question—that is: that before any analysis it is already articulated in discrete elements. This is crucial, because these elements are those that linguistic analysis instructs us to isolate as signifiers, and here they are grasped in their function in its pure state at the point that is both the most implausible and the most plausible:

– the most implausible, since their chain persists in an otherness with respect to the subject as radical as that of hieroglyphs still undeciphered in the solitude of the desert;

– the most plausible, because only there can their function of inducing meaning in the signified, by imposing their structure on it, appear unambiguously.

For indeed the furrows opened by the signifier in the real world seek to widen the breaches it offers to them as being, to the point that an ambiguity may remain as to whether the signifier does not there follow the law of the signified.

But it is not the same on the level of the putting into question, not of the subject’s place in the world, but of his existence as subject, a putting into question that, starting from him, will extend to his intramundane relation to objects, and to the existence of the world insofar as it too can be called into question beyond its order.

4. It is crucial to observe in the experience of the unconscious Other, where Freud guides us, that the question does not find its outlines in protomorphic proliferations of the image, in vegetative swellings, in soulful fringes radiating from the pulsations of life.

This marks the entire difference of his orientation from that of Jung’s school, which clings to such forms: Wandlungen der Libido. These forms can be brought to the foreground of a mantic, for they can be produced by appropriate techniques (promoting imaginary creations: reveries, drawings, etc.) in a site that is locatable here: one sees it on our schema, stretched between a and a’, that is, in the veil of the narcissistic mirage, eminently suited to sustain by its effects of seduction and capture all that comes to be reflected in it.

If Freud rejected this mantic, it is at the point where it neglected the guiding function of a signifying articulation, which takes effect from its internal law and from a material subjected to the essential poverty that defines it.

Just as it is to the extent that this style of articulation has been maintained, by virtue of the Freudian word—even dismembered—within the community that claims to be orthodox, that a difference persists, as deep, between the two schools, although at the point things have now reached, neither is capable of articulating the reason for it. By which measure the level of their practice will soon appear to be reducible to the distance between the styles of reverie of the Alps and the Atlantic.

To return to the phrase that so delighted Freud in Charcot’s mouth, “this does not prevent the Other from existing” at its place A.

For remove it, and man can no longer even sustain himself in the position of Narcissus. The anima, as by the effect of an elastic, snaps back onto the animus, and the animus onto the animal, which between S and a sustains with its Umwelt “external relations” noticeably tighter than ours, though one cannot say that its relation to the Other is null—only that it appears to us only in sporadic sketches of neurosis.

5. The L of the putting-into-question of the subject in his existence has a combinatory structure that must not be confused with its spatial aspect. In this respect, it is truly the signifier itself which must be articulated in the Other, and especially in its topology of the quaternary.

To support this structure, we find within it the three signifiers in which the Other may be identified in the Oedipus complex. They suffice to symbolize the meanings of sexual reproduction, under the signifiers of the relation of love and procreation.

The fourth term is given by the subject in his reality, as such foreclosed from the system and entering only under the mode of the dead into the play of signifiers, but becoming the true subject insofar as this play of signifiers comes to make him signify.

This play of signifiers is indeed not inert, since it is animated in each particular part by the entire history of the ancestry of the other reals that the naming of the Other signifiers implies in the contemporaneity of the Subject. Even more, this play, insofar as it institutes itself as rule beyond each part, already structures within the subject the three instances—ego (ideal), reality, superego—whose determination will be the work of Freud’s second topology.

The subject, moreover, enters the game as dead, but it is as living that he will play it, it is in his life that he must take on the color he occasionally announces there. He will do so by using a set of imaginary figures, selected from among the countless forms of anima-like relations, and whose choice involves a certain arbitrariness, since to homologously cover the symbolic ternary, it must be numerically reduced.

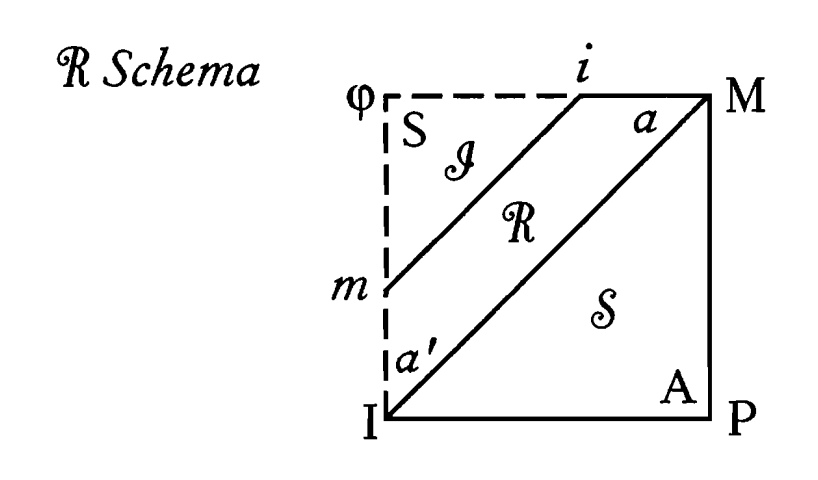

To do this, the polar relation by which the specular image (of the narcissistic relation) is linked as unifying to the set of imaginary elements known as the fragmented body provides a pair which is not only naturally suited, by its development and structure, to serve as the homologue of the symbolic Mother–Child relation. The imaginary pair of the mirror stage, by what it manifests of what is against nature—if one must relate it to a specific prematuration of birth in humans—proves appropriate to give to the imaginary triangle the base that the symbolic relation may in some way cover. (See schema R).

Indeed, it is through the gap opened by this prematuration in the imaginary and where the effects of the mirror stage abound, that the human animal is capable of imagining itself as mortal—not that one could say it would be capable of doing so without its symbiosis with the symbolic, but rather that without this gap, which alienates it to its own image, that symbiosis with the symbolic could not have occurred, wherein it constitutes itself as subject to death.

6. The third term of the imaginary ternary, the one where the subject identifies himself, in opposition, with his being as living, is nothing other than the phallic image, whose unveiling in this function is not the least scandal of the Freudian discovery.

Let us now inscribe here, by way of conceptual visualization of this double ternary, what we will henceforth call schema R, which represents the conditioning lines of the perceptum, in other words of the object, insofar as these lines circumscribe the field of reality, far from merely depending on it.

Thus, by considering the vertices of the symbolic triangle: I as the ego ideal, M as the signifier of the primordial object, and P as the position in A of the Name-of-the-Father, one can grasp how the homological pinning of the subject S’s signification under the signifier of the phallus may affect the support of the field of reality, delimited by the quadrangle MimI. The two other vertices of the latter, i and m, representing the two imaginary terms of the narcissistic relation, that is, the ego and the specular image.

One may thereby locate from i to M, or at a, the ends of the segments Si, Sa1, Sa2, San, SM, where the figures of the imaginary other are placed in the erotic-aggressive relations where they are realized—just as from m to I, or at a’, the ends of the segments Sm, Sa1, Sa2, San, SI, where the ego identifies, from its specular Urbild to the paternal identification of the ego ideal.

Those who followed our seminar in the year 1956–57 know the use we made of the imaginary ternary here posited, in which the child as desired actually constitutes the vertex I, in order to restore to the notion of Object Relation—somewhat discredited by the accumulation of foolishness recently asserted under its heading—the capital of experience legitimately associated with it.

This schema, indeed, makes it possible to demonstrate the relations that refer not to the pre-Oedipal stages—which are, of course, not nonexistent, but analytically unthinkable (as the faltering yet guided work of Mrs. Melanie Klein sufficiently demonstrates)—but to the pregenital stages insofar as they are ordered in the retroaction of the Oedipus.

The entire problem of perversions consists in conceiving how the child, in his relation to the mother—a relation constituted in analysis not by his vital dependence, but by his dependence on her love, that is, by the desire of her desire—identifies with the imaginary object of that desire, insofar as the mother herself symbolizes it in the phallus.

The phallocentrism produced by this dialectic is all that we have to retain here. It is, of course, entirely conditioned by the intrusion of the signifier into the human psyche, and strictly impossible to deduce from any pre-established harmony of said psyche with the nature it expresses.

This imaginary effect, which can only be felt as discordance in the name of the prejudice of an instinct’s inherent normativity, nevertheless determined the long controversy—now extinguished, though not without damage—concerning the primary or secondary nature of the phallic phase. Were it not for the extreme importance of the issue, this controversy would deserve our attention for the dialectical feats it forced Dr. Ernest Jones to perform in order to support, while affirming his complete agreement with Freud, a position diametrically opposed to his—that is, one that made him, with nuances no doubt, the champion of English feminists devoted to the principle of “to each their own”: the boys get the phallus, the girls get the c…

7. This imaginary function of the phallus was thus revealed by Freud as the pivot of the symbolic process that completes, in both sexes, the questioning of sex through the castration complex.

The current obscuring of this function of the phallus (reduced to the role of a partial object) in the psychoanalytic discourse is only the continuation of the deep mystification in which culture maintains its symbol—this is to be understood in the sense that even paganism only produced it at the end of its most secret mysteries.

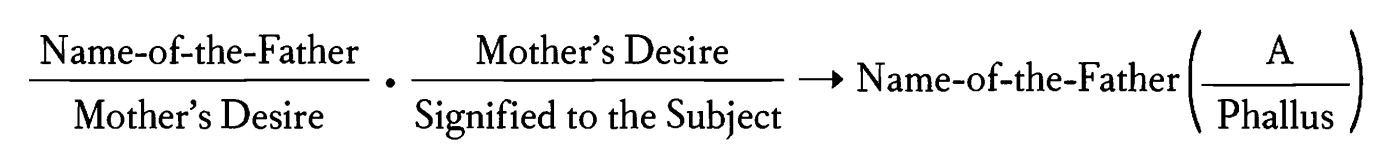

Indeed, within the subjective economy, as we see it governed by the unconscious, it is a meaning that is evoked only by what we call a metaphor—specifically, the paternal metaphor.

And this brings us back, since it is with Mrs. Macalpine that we have chosen to dialogue, to her need for a reference to a “heliolithism,” by which she claims to see procreation codified in a pre-Oedipal culture, where the procreative function of the father would be eluded.

Everything that might be advanced in this direction, in whatever form, will only serve all the more to highlight the function of the signifier that conditions paternity.

For in another debate from the time when psychoanalysts still questioned doctrine, Dr. Ernest Jones, with a more pertinent remark than elsewhere, did not bring an argument any less inappropriate.

Regarding the state of beliefs in some Australian tribe, he refused to admit that any human collective could ignore the empirical fact that, barring enigmatic exceptions, no woman gives birth without having had coitus, nor be unaware of the interval required between the antecedent and the event. Now, this credit—which seems to us perfectly legitimate when granted to the human capacity to observe reality—is precisely what has no importance whatsoever in the matter.

For if the symbolic context requires it, paternity will nonetheless be attributed to the woman’s encounter with a spirit at a certain fountain or within a particular monolith where the spirit is supposed to reside.

This is exactly what demonstrates that the attribution of procreation to the father can only be the effect of a pure signifier—of a recognition not of the real father, but of what religion has taught us to invoke as the Name-of-the-Father.

No signifier is, of course, needed to be a father, any more than to be dead—but without a signifier, no one will ever know anything of either of these states of being.

I recall here, for the benefit of those who cannot be persuaded to seek in Freud’s texts a complement to the enlightenment their instructors dispense, how insistently the affinity is underlined therein between the two signifying relations we have just evoked, whenever the neurotic subject (particularly the obsessive) manifests it through the conjunction of their themes.

How could Freud fail to recognize it, since the necessity of his reflection led him to link the appearance of the signifier of the Father, as author of the Law, to death—indeed, to the murder of the Father—thus showing that, if this murder is the fertile moment of the debt through which the subject is bound for life to the Law, the symbolic Father, insofar as he signifies this Law, is indeed the dead Father.

IV. On Schreber’s Side.

1. We can now enter into the subjectivity of Schreber’s delusion.

The meaning of the phallus, we have said, must be evoked in the subject’s imaginary by the paternal metaphor.

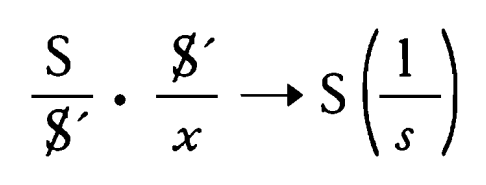

This has a precise sense within the economy of the signifier, whose formalization we can here only briefly recall—familiar to those who follow our current seminar on the formations of the unconscious. Namely: the formula of metaphor, or of signifying substitution:

where the capital S’s are signifiers, x is the unknown signification, and s is the signified induced by the metaphor, which consists in the substitution in the signifying chain of S for S’. The elision of S’, here represented by its erasure, is the condition for the success of the metaphor.

This applies, then, to the metaphor of the Name-of-the-Father—that is, the metaphor that substitutes this Name in the place first symbolized by the operation of the absence of the mother.

Let us now try to conceive a subjective situation in which, to the call of the Name-of-the-Father, there responds not the absence of the real father—for that absence is more than compatible with the presence of the signifier—but the lack of the signifier itself.

This is not a conception for which we are unprepared. The presence of the signifier in the Other is, in fact, a presence ordinarily closed to the subject, since it is usually in the repressed (verdrängt) state that it persists there, and from there insists on representing itself in the signified through its automatism of repetition (Wiederholungszwang).

Let us extract from several of Freud’s texts a term that is articulated in them clearly enough that they would be unjustifiable if it did not designate a function of the unconscious distinct from that of repression. Let us take as demonstrated what was the core of my seminar on psychoses, namely, that this term refers to the most necessary implication of his thought when it engages with the phenomenon of psychosis: it is the term Verwerfung.

It is articulated in this register as the absence of that Bejahung, or judgment of attribution, which Freud posits as a necessary antecedent to any possible application of Verneinung, which he opposes to it as a judgment of existence: and the entire article in which he isolates this Verneinung as an element of the analytic experience shows that it involves the avowal of the very signifier it cancels.

Therefore, the primordial Bejahung also bears on the signifier, and other texts allow us to recognize this, most notably letter 52 of the correspondence with Fliess, where the signifier is expressly isolated as the term of an original perception, under the name of sign (Zeichen).

We shall therefore regard Verwerfung as foreclosure of the signifier. At the point where, as we shall see, the Name-of-the-Father is called, there may answer in the Other a pure and simple hole, which, through the failure of the metaphorical effect, will produce a corresponding hole at the place of phallic signification.

This is the only form under which we are able to conceive what Schreber presents to us as the outcome of a damage he is only able to partially disclose, and in which, he says, with the names of Flechsig and Schreber, the term “murder of souls” (Seelenmord: p. 22-II) plays an essential role¹³.

It is clear that what is at stake here is a disorder provoked at the most intimate joint of the subject’s feeling of life, and the censorship that mutilates the text before the addition that Schreber announces to the rather circuitous explanations he attempted of his process, suggests that he associated with the names of living persons, facts that the conventions of the time could barely tolerate being published. Indeed, the entire following chapter is missing, and Freud, in order to exercise his insight, had to content himself with the allusion to Faust, Der Freischütz, and Byron’s Manfred, the last of which (from which he supposes the name Ahriman to be borrowed—one of the apophanies of God in Schreber’s delusion) seemed to him to take on its full value in this reference from its theme: the hero dies from the curse carried within him by the death of the object of an incestuous love between siblings.

As for us, since with Freud we have chosen to place our trust in a text which—aside from these regrettable mutilations—remains a document whose guarantees of credibility are equal to the highest, it is within the most developed form of the delusion with which the book is entirely bound up that we will seek to show a structure, one that will prove to resemble the very process of psychosis.

2. Along this path, we will note, with the nuance of surprise in which Freud recognizes the subjective connotation of the unconscious, that delusion unfolds its entire tapestry around the creative power attributed to words, whose divine rays (Gottesstrahlen) are the hypostasis.

It begins like a leitmotif in the first chapter: where the author first pauses on how the act of bringing an existence into being from nothing strikes the mind as shocking, contradicting the evidence provided to thought by experience in the transformations of a matter in which reality finds its substance.

He heightens this paradox by contrasting it with ideas more familiar to man, whom he assures us he is, as if that needed saying: a gebildet German of the Wilhelmine era, nurtured by Haeckelian metascientism, in support of which he provides a reading list—an opportunity for us to supplement, by referring to it, what Gavarni somewhere calls a bold idea of Man¹⁴.

It is even this reflected paradox of the intrusion of a thought that had until then been unthinkable for him, wherein Schreber sees the proof that something must have occurred that did not originate in his own mind—a proof which, it seems, only the petitions of principle previously exposed in the psychiatrist’s stance could entitle us to resist.

3. That said, for our part, let us confine ourselves to a sequence of phenomena that Schreber lays out in his fifteenth chapter (pp. 204–215).

It is understood by this point that the maintenance of his position in the forced game of thought (Denkzwang) imposed upon him by God’s words (see above, I-5), has a dramatic stake: namely that God—whose power of misrecognition we shall address later—regards the subject as annihilated and leaves him stuck or cast aside (liegen lassen), a threat to which we shall return.

That the effort of response upon which the subject is thus suspended—let us say, in his very being as subject—should momentarily fail in a thinking-of-nothing (Nichtsdenken), which seems to him to be the most humanly justifiable form of rest (Schreber dicit), here is what occurs according to him:

- what he calls the miracle of screaming (Brüllenwunder), a cry torn from his chest that surprises him beyond any warning, whether alone or in front of an audience horrified by the image of his mouth suddenly gaping open on an unspeakable void, dropping the cigar that had been just affixed to it moments before;

- the cry for help (“Hülfe rufen”), emitted from “divine nerves detached from the mass,” and whose plaintive tone arises from the great distance to which God withdraws;

(two phenomena in which subjective tearing is so indistinguishable from its signifying mode that we shall not dwell on them);

- the imminent emergence, either in the occult zone of the perceptual field—in the hallway, in the neighboring room—of manifestations that, though not extraordinary, impose themselves on the subject as produced with him in mind;

- the appearance, on the next level of remoteness—beyond the reach of the senses, in the park, in the real—of miraculous creations, that is, newly created beings, creations which Mrs. Macalpine astutely notes always belong to flying species: birds or insects.

Do not these final meteors of the delusion appear as the trace of a wake, or as a fringe effect, indicating the two moments in which the signifier, fallen silent in the subject, causes from its night first a glimmer of meaning to burst forth at the surface of the real, then makes the real itself light up with a radiance projected from beneath its substructure of nothingness?

Thus, at the very point of hallucinatory effects, these creatures—who, if we were to apply the criterion of the phenomenon’s occurrence in reality rigorously, alone deserve the title of hallucinations—compel us to reconsider, in their symbolic solidarity, the triad of the Creator, the Creature, and the Created, which here emerges.

4. It is from the position of the Creator, in fact, that we will ascend to that of the Created, who subjectively creates it.

Unique in his Multiplicity, Multiple in his Unity (such are the attributes, reminiscent of Heraclitus, by which Schreber defines him), this God, in fact split into a hierarchy of realms that would in itself merit a full study, degrades into beings who pilfer identities that have been disannexed.

Immanent in these beings—whose capture through their inclusion in Schreber’s being threatens his integrity—God is not without an intuitive support of a hyperspace, in which Schreber even perceives signifying transmissions as conducted along threads (Fäden), which materialize the parabolic trajectory by which they enter his skull through the occiput (p. 315–Postscript V).

Nevertheless, as time goes on, God allows the field of beings without intelligence to extend ever further beneath his manifestations—beings who do not know what they are saying, beings of inaneness, such as those miraculously created birds, those talking birds, those vestibules of heaven (Vorhöfe des Himmels), in which Freud’s misogyny detected at first glance the “white geese” that young girls were in the ideals of his era, only to be confirmed in this by the proper names¹⁵ the subject later assigns to them. Let us say only that they are, for us, far more representative in the surprise effect they provoke through the similarity of vocables and the purely homophonic equivalences they rely on for their use (Santiago = Carthago, Chinesenthum = Jesum Christum, etc., S. XV-210).

In the same measure, the being of God in his essence withdraws ever further into the space that conditions him—a withdrawal that is intuited in the growing slowness of his speech, slowing to the point of a stammered spelling-out (S. 223-XVI). So that, were we to follow only the indications of this process, we would take this unique Other, to whom the subject’s existence is articulated, to be one whose main function is to empty the places (S. note 196-XIV) where the rustling of words unfolds—if Schreber did not take care to further inform us that this God is foreclosed from every other aspect of exchange. He does so while excusing himself, but however much he may regret it, he must acknowledge the fact: God is not only impermeable to experience; he is incapable of understanding living man; he grasps him only from the outside (which indeed seems to be his essential mode); all interiority is closed off to him. A “system of notes” (Aufschreibesystem) in which acts and thoughts are preserved recalls, to be sure, in a rather slippery fashion, the notebook kept by the guardian angel of our catechized childhoods—but beyond that, let us note the total absence of any probing of hearts or loins (S. I. 20).

Thus, once the purification of souls (Läuterung) will have abolished in them all persistence of personal identity, all will be reduced to the eternal subsistence of this verbiage, through which alone God has access to the works that human ingenuity constructs (S. 300-P.S. II).

How can one fail to notice here that the great-nephew of the author of Novae species insectorum (Johann-Christian-Daniel von Schreber) emphasizes that none of the miracle creatures belongs to a new species—and to add that, contrary to Mrs. Macalpine, who sees in them the Dove that, from the bosom of the Father, carries toward the Virgin the fruitful message of the Logos, they remind us rather of those conjured by an illusionist from the opening of his vest or his sleeve?

By which we are finally brought to marvel that the subject in the grip of such mysteries does not doubt, though he is a Created being, either his ability to counter the disarming foolishness of his Lord with his own words, or his capacity to hold out—despite and against the destruction that he believes his Creator capable of unleashing upon him as well as upon anyone, by a right which is founded for him in the name of the order of the Universe (Weltordnung)—a right which, being on his side, justifies this unique example of the victory of a creature whom a chain of disorders has brought under the blow of the “perfidy” of his creator. (“Perfidy,” the word released, not without reservation, is in French: S. 226-XVI.)

Is this not, then, a strange counterpoint to Malebranche’s doctrine of continuous creation, this recalcitrant Created being, who sustains himself against his fall solely by the support of his own speech and by his faith in the Word?

It would surely be worth another round with the authors of the bac de philo, among whom we may have too readily scorned those outside the track of manufacturing the psychological Everyman with whom our time believes it has measured humanism—don’t you think?—perhaps a little flatly.

From Malebranche or from Locke,

The cleverer is the more baroque…

Yes, but which one is it? That’s the rub, my dear colleague. Come now, drop that stiff expression. When, then, will you feel at ease where you are truly at home?

5. Let us now attempt to transpose the position of the subject as it is constituted here in the symbolic order onto the ternary structure that locates it in our schema R.

It seems clear to us then that if the Created I assumes in P the place left vacant by the Law, the place of the Creator is designated in that fundamental liegen lassen—that leaving aside—where the absence, stripped bare by the foreclosure of the Father, appears, which allowed the primordial symbolization M of the Mother to be constructed.

From one to the other, a line that would culminate in the Creatures of speech—occupying the place of the child denied to the subject’s hopes (see below: Postscript)—may thus be conceived as bypassing the hole dug in the field of the signifier by the foreclosure of the Name-of-the-Father (see Schema I, p. 39).

It is around this hole, where the support of the signifying chain is missing for the subject, and which, as one sees, does not need to be ineffable to be panic-inducing, that the entire struggle in which the subject reconstructed himself was played out. He led this struggle with honor, and the vaginas of heaven (another meaning of the word Vorhöfe, see above), the miraculous young girls who besieged the edges of the hole in their cohort, rendered its gloss in the clucking admiration torn from their harpy throats: “Verfluchter Kerl!” “Damned boy!” In other words: he’s a tough bunny. Alas! It was by antiphrasis.

6. For already, and earlier, a gaping wound had opened for him in the imaginary field, corresponding to the failure of symbolic metaphor, one which could only be resolved in the fulfillment of the Entmannung (emasculation).

An object of horror at first for the subject, then accepted as a reasonable compromise (vernünftig, S. 177-XIII), it became henceforth an irrevocable decision (S. note p. 179-XIII), and a future motive for a redemption concerning the universe.

If we are not thereby done with the term Entmannung, it will surely trouble us less than it does Mrs. Ida Macalpine in the position that we have described as hers. No doubt she thinks to bring order by substituting the word unmanning for the word emasculation, which the translator of Volume III of the Collected Papers had innocently believed sufficient to render it, even seeking to ensure that this translation would not be retained in the authorized edition in preparation. Perhaps she preserves in it some imperceptible etymological nuance, through which these terms might be distinguished—though they are in fact used interchangeably¹⁶.

But to what end? Mrs. Macalpine, rejecting as improper¹⁷ any questioning of an organ which, if we go by the Memoirs, she sees as destined only for peaceful resorption into the subject’s innards—does she mean to present us with the cowardly withdrawal to which it retreats when he shivers, or the conscientious objection lingered over with such mischief by the author of the Satyricon?

Or might she actually believe that the complex bearing the same name ever concerned a real castration?

She is certainly justified in pointing out the ambiguity involved in equating the transformation of the subject into a woman (Verweiblichung) with emasculation (for that is indeed the meaning of Entmannung). But she fails to see that this ambiguity belongs to the very structure of subjectivity, which produces it here: a structure in which what borders at the imaginary level on the transformation of the subject into a woman is precisely what causes him to fall from any inheritance by which he might legitimately expect the assignment of a penis to his person. This, for the reason that if being and having are in principle mutually exclusive, they nonetheless become confused—at least in terms of outcome—when it comes to a lack. This does not, however, prevent their distinction from being decisive for what follows.

As can be seen by observing that it is not because the penis is foreclosed that the patient is destined to become a woman, but because he must be the phallus.

The symbolic parity Mädchen = Phallus, or in English the equation Girl = Phallus, as expressed by Mr. Fenichel¹⁸, who takes it as the theme for a meritorious—if somewhat muddled—essay, has its root in the imaginary pathways through which the child’s desire finds a way to identify with the mother’s lack-of-being, to which she herself, of course, was introduced by the symbolic law in which this lack is constituted.

It is the same mechanism that causes women in reality to serve—however displeasing to them—as objects for the exchanges governed by the elementary structures of kinship, which occasionally persist in the imaginary, while what is transmitted in parallel within the symbolic order is the phallus.

7. Here, the identification—whatever it may be—by which the subject has assumed the mother’s desire, once shaken, triggers the dissolution of the imaginary tripod (notably, it is in his mother’s apartment, where he has taken refuge, that the subject experiences his first episode of anxious confusion with a suicide raptus: S. 39–40-IV).

Undoubtedly, the divination of the unconscious had very early on warned the subject that, failing to be the phallus that the mother lacks, the solution remained for him to become the woman who is lacking to men.

That is even the meaning of the fantasy whose account has been widely noted in his writing and which we cited earlier from the incubation period of his second illness, namely, the idea “that it would be beautiful to be a woman undergoing copulation.” This pont-aux-ânes [schoolboy cliché] of Schreberian literature pins itself here in its rightful place.

Yet this solution was, at that point, premature. For the Menschenspielerei (a term appearing in the fundamental language, that is, in contemporary language: monkey business among men) that was supposed to follow naturally, one could say that the call to arms fell flat, for the reason that these “braves” proved as improbable as the subject himself—just as devoid of any phallus. It is that, in the subject’s imaginary, the trait parallel to the tracing of their figure—visible in a drawing by little Hans and familiar to those who study children’s drawings—was omitted not only for him but for them as well. For the others were henceforth nothing more than “hastily sketched images of men,” or in a more literal rendering of flüchtig hingemachte Männer, “men cobbled together on the fly”—combining Mr. Niederland’s remarks on hinmachen with Édouard Pichon’s idiomatic feel for French usage¹⁹. So the matter seemed on track to stagnate quite ingloriously, had the subject not found a brilliant way to redeem it.

He himself articulated the outcome (in November 1895, two years after the onset of his illness) under the name Versöhnung: the word carries the meanings of atonement, appeasement, and—given the characteristics of the fundamental language—should be drawn even closer to the original sense of Sühne, that is, sacrifice, even though it is often emphasized as meaning compromise (a compromise of reason, cf. p. 32, by which the subject justifies the acceptance of his fate).

Here, Freud—going far beyond the rationalization of the subject himself—paradoxically accepts that the reconciliation (since this is the flat meaning chosen in French), of which the subject speaks, finds its basis in the bargaining of the partner it involves, namely in the consideration that the spouse of God contracts in any case an alliance capable of satisfying the most demanding self-esteem.

We believe we may say that Freud here failed by his own standards, and in the most contradictory way—namely, that he accepted as the turning point of the delusion what he had rejected in his general conception: that is, to make the homosexual theme dependent on the idea of grandeur (we give our readers credit for knowing his text).

This failure has its explanation in necessity, in the fact that Freud had not yet formulated the Introduction to Narcissism.

8. Undoubtedly, three years later (1911–1914), he would not have missed the real spring behind the reversal of the position of indignation, which the idea of Entmannung initially provoked in the subject: namely, that in the meantime, the subject had died.

At least, that is the event that the voices—always well-informed and unfailingly consistent in their reporting—revealed to him after the fact, complete with date and the name of the newspaper in which the obituary had appeared (S. 81–VII).

As for us, we may content ourselves with the testimony provided by the medical certificates, which show us, at the appropriate moment, the picture of the patient plunged into catatonic stupor.

His memories of this moment, as usual, are not lacking. Thus we know that, deviating from the custom whereby one enters death feet first, our patient, crossing it only in transit, delighted in positioning himself with his feet sticking out—namely, out the window—under the suggestive pretext of seeking fresh air (S. 172–XII), perhaps thereby repeating (we leave this for those who will concern themselves only with the imaginary avatar) the presentation of his birth.

But this is not a career one resumes at the fully counted age of fifty without experiencing some disorientation. Hence the faithful portrait that the voices—annalists, let us say—gave him of himself as a “leprous corpse leading another leprous corpse” (S. 92-VII), a rather brilliant description, one must admit, of an identity reduced to confrontation with its psychic double, but which also makes manifest the regression of the subject—not genetic but topological—to the mirror stage, insofar as the relation to the specular other is reduced there to its mortal edge.

This was also the time when his body was nothing but an aggregate of colonies of foreign “nerves,” a kind of dumping ground for fragments detached from the identities of his persecutors (S. XIV).

The relation of all this to homosexuality, clearly manifest in the delusion, seems to us to require a more rigorous regulation of the use that can be made of this reference in theory.

The interest is considerable, since it is certain that the use of this term in interpretation can cause serious harm if it is not clarified by the symbolic relations we hold here to be decisive.

9. We believe that this symbolic determination is demonstrated in the form in which the imaginary structure comes to be restored. At this stage, it presents two aspects that Freud himself distinguished.

The first is that of a transsexualist practice, by no means unworthy of being compared to the “perversion” whose traits have since been clarified by numerous observations²⁰.

Moreover, we must point out what the structure we outline here can reveal about the quite singular insistence shown by the subjects of these observations in seeking, for their most radically corrective demands, the authorization—or even, so to speak, the hands-on participation—of their father.

Be that as it may, we see our subject surrendering himself to an erotic activity, which he emphasizes is strictly reserved for solitude, but from which, nonetheless, he admits deriving satisfactions—namely, those given to him by his image in the mirror when, adorned with the trappings of feminine finery, nothing, he says, in the upper part of his body seems to him unsuited to convincing any potential admirer of its feminine bust (S. 280-XXI).

To this, it seems appropriate to link the development, alleged as endosomatic perception, of the so-called nerves of feminine voluptuousness in his own skin—specifically in the zones said to be erogenous in women.

One remark, namely that through constant attention to contemplating the image of the woman, through never detaching his thought from the support of something feminine, divine voluptuousness would be all the more fulfilled—this remark turns us toward the other aspect of libidinal fantasies.

This latter links the feminization of the subject to the coordinate of divine copulation.

Freud clearly saw the mortifying sense of this, highlighting everything that ties the “voluptuousness of the soul” (Seelenwollust) it includes to “beatitude” (Seligkeit), insofar as this is the state of departed souls (abschiedenen Wesen).

That the now-blessed voluptuousness has become soul-beatitude is indeed an essential turning point, whose linguistic motivation Freud, let us note, underlines by suggesting that the history of his language might perhaps shed light on it²¹.

This is merely to mistake the dimension in which the letter manifests in the unconscious, and which, according to its specific instance as letter, is far less etymological (precisely diachronic) than homophonic (precisely synchronic). For there is nothing in the history of the German language that allows one to connect selig with Seele, nor the happiness that lifts lovers “to the heavens”—to the extent that this is what Freud evokes in the aria he quotes from Don Juan—with that which the abode of heaven promises to the so-called blessed souls. The deceased are selig in German only by borrowing from Latin, and because in that language their memory was called blessed (beatae memoriae, seliger Gedächtnis). Their Seelen have more to do with the lakes (Seen) in which they once lingered than with anything of their beatitude. What remains is that the unconscious cares more for the signifier than for the signified, and that “the late my father” may mean there that he was the fire of God—or even command against him the order: fire!

Once this digression is passed, it remains that we are here in a beyond-the-world that accommodates itself quite well to an indefinite postponement of the realization of its goal.

Indeed, when Schreber will have completed his transformation into a woman, the act of divine fertilization will take place, which it is clearly understood (S. 3–Introduction) that God could not carry out by any obscure progression through organs. (Let us not forget God’s aversion toward the living.) It is thus by a spiritual operation that Schreber will feel the embryonic germ awaken within him, the same one whose trembling he had already experienced at the onset of his illness.