🦋🤖 Robo-Spun by IBF 🦋🤖

🍂🏚️🪪 Haymatlos 🍂🏚️🪪

(Turkish)

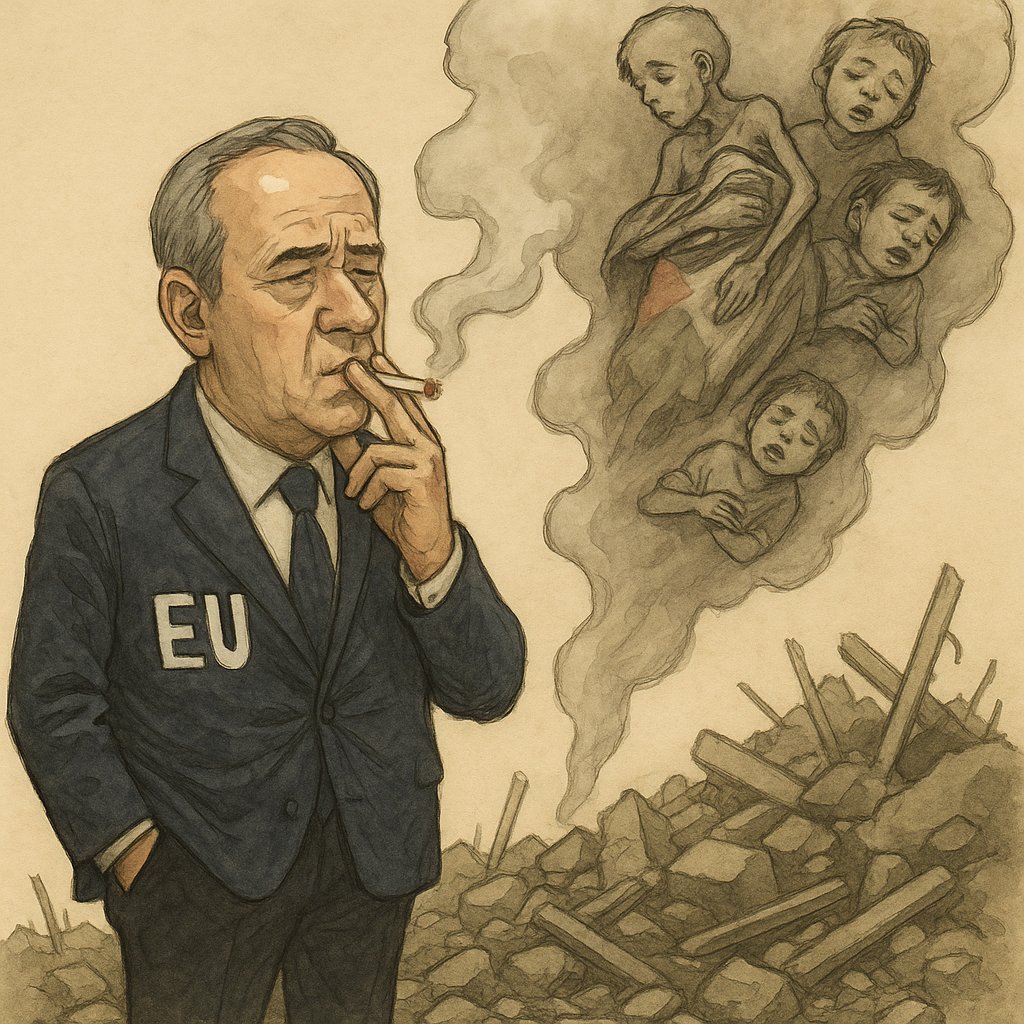

They say “Never again.” But the way they say it now—blandly, bureaucratically, half-mouthed and fully catered—is indistinguishable from “One last time, and we really mean it.” In Europe’s moral economy, where irony has long gone from literary tool to institutional policy, “Never again” has become the solemn chant of yet another again. It’s a chant that echoes through Brussels as children die under rubble in Rafah, and heads nod sagely in Strasbourg while tank shells rewrite the concept of shelter in Khan Younis.

The genocide in Palestine is not a break from Europe’s post-Holocaust ethics—it is their culmination. This is not a contradiction; it is the precise mechanism Žižek identifies in his reading of capitalism’s perverse embrace of critique. What better way to preserve the sanctity of European self-image than by incorporating guilt into the spectacle, layering the horror with legalese and sorrowful regret, all the while continuing to bankroll the machinery?

Let’s be honest: Europe, like Zeno from Svevo’s Zeno’s Conscience, is addicted. Addicted to moral superiority, addicted to selective memory, addicted to the melancholic enjoyment of its own humanitarian tragedies. It’s been saying “This is the last cigarette” since 1945. Bosnia? Last cigarette. Rwanda? Definitely the last. Iraq? Afghanistan? Libya? Syria? “I know I said that was the last one, but this one really is.”

And now Palestine.

We’re watching the same ritual unfold. European politicians puff on their performative outrage, their eyes misting over as they declare Israel’s right to self-defense in the exact cadence that once declared colonial right to civilize. “We will never allow antisemitism again,” they say, while handing the ashtray to the IDF. “To be clear, this bombing of schools and hospitals is deeply regrettable… but,” they pause, nostrils flaring, cigarette poised, “antisemitism is the real threat.”

Because here’s the twist: in the labyrinth of liberal European morality, to call genocide genocide—when it’s being committed by a state imagined as the avatar of Holocaust memory—is itself treated as the return of the crime. So in a grim psychoanalytic joke, the true descendant of Auschwitz becomes… the Palestinian child in Rafah, their last breath choked out under rubble funded by German guilt and French silence.

The logic is airtight, Kafkaesque: genocide denial now parades in the robes of genocide prevention. You want to speak of war crimes? Ah, but that’s antisemitic. Want to cite the Genocide Convention? How dare you weaponize memory. In this house, Europe says, we remember the Holocaust by ignoring its repetition.

And so, just as Zeno was instructed to stop trying to quit smoking, Europe has apparently decided to stop trying to quit genocides. It no longer even pretends that stopping matters—only that the performance of stopping continues. They pass resolutions, hold conferences, light candles, rename boulevards after Anne Frank—while Gaza is bulldozed into a new Yad Vashem of living stone and smoldering flesh.

This is not policy failure. This is not ignorance. It is a grotesque farce, the kind of moral burlesque that only the most culturally refined imperialism could produce. This genocide isn’t an aberration of Europe’s values—it is their endgame. It is the point where all the bureaucratic euphemisms, all the solemn museum tours, all the EU-funded human rights reports dissolve into the final puff of that long-fetishized cigarette: genocide, just one last time.

And what a cigarette it is. Rolled in the sacred paper of Jewish suffering, lit by the phosphorous of Western ordinance, inhaled deeply in Paris, Berlin, and The Hague. Each drag a conference. Each ash a press release. The nicotine buzz? That’s the soothing sense of moral complexity—ah, yes, the bliss of tragic impasse, where all sides are guilty and none are responsible. Perfect for dinner parties.

But here’s the truth, and it doesn’t need diplomacy to say it: Europe is smoking Gaza. And like Zeno, it may only stop when the act itself becomes so emptied of pleasure, so saturated with guilt and failure and despair, that there is nothing left to inhale. When the child in the rubble ceases to even signify shame, when the last building falls and no metaphor will hold, perhaps then, in the smog of ashes and irony, Europe will stub out its conscience at last.

But don’t bet on it. After all, there’s always one more last cigarette.

Die letzte Zigarette Europas: Eine tragikomische Chronik der Völkermord-Reinwaschung

Sie sagen: „Nie wieder.“ Aber so wie sie es heute sagen – fad, bürokratisch, halbherzig und voll verpflegt – ist es nicht zu unterscheiden von: „Ein letztes Mal, und diesmal meinen wir es wirklich.“ In Europas moralischer Ökonomie, wo Ironie längst vom literarischen Mittel zur institutionellen Politik geworden ist, ist „Nie wieder“ zum feierlichen Mantra eines weiteren „Doch wieder“ geworden. Es hallt durch Brüssel, während in Rafah Kinder unter Trümmern sterben, und nickende Köpfe in Straßburg mit weiser Miene zustimmen, während Panzergeschosse in Khan Younis das Konzept von Schutz neu definieren.

Der Völkermord in Palästina ist kein Bruch mit Europas post-holocaustischer Ethik – er ist ihre Vollendung. Das ist kein Widerspruch; es ist genau jener Mechanismus, den Žižek in seiner Analyse der pervertierten Umarmung der Kritik durch den Kapitalismus beschreibt. Was könnte das europäische Selbstbild besser heiligen als Schuld in das Spektakel zu integrieren, den Horror in juristische Floskeln und wehmütige Reue zu kleiden – und gleichzeitig weiter die Maschinerie zu finanzieren?

Seien wir ehrlich: Europa ist süchtig – wie Zeno in Svevos Zenos Gewissen. Süchtig nach moralischer Überlegenheit, süchtig nach selektiver Erinnerung, süchtig nach dem melancholischen Genuss eigener humanitärer Tragödien. Es sagt seit 1945: „Das ist die letzte Zigarette.“ Bosnien? Letzte Zigarette. Ruanda? Definitiv die letzte. Irak? Afghanistan? Libyen? Syrien? „Ich weiß, ich habe gesagt, das war die letzte – aber diese hier ist es wirklich.“

Und jetzt: Palästina.

Wir erleben dasselbe Ritual wieder. Europäische Politiker:innen ziehen an ihrer performativen Empörung, die Augen feucht, wenn sie Israels Recht auf Selbstverteidigung in exakt dem Tonfall deklarieren, mit dem einst das koloniale Recht zu zivilisieren verkündet wurde. „Wir werden nie wieder Antisemitismus zulassen“, sagen sie, während sie dem IDF den Aschenbecher reichen. „Um es klar zu sagen, diese Bombardierung von Schulen und Krankenhäusern ist zutiefst bedauerlich… aber“, kurze Pause, geblähte Nüstern, Zigarette gezückt, „der wahre Feind ist der Antisemitismus.“

Denn hier ist die Pointe: Im Labyrinth liberaler europäischer Moral wird das Benennen eines Völkermords – wenn er von einem Staat begangen wird, der als Verkörperung der Holocaust-Erinnerung gilt – selbst als Rückkehr des Verbrechens behandelt. In einem düsteren psychoanalytischen Witz wird das wahre Kind von Auschwitz… das palästinensische Kind in Rafah, dessen letzter Atem unter Trümmern erstickt, finanziert durch deutsche Schuld und französisches Schweigen.

Die Logik ist wasserdicht, kafkaesk: Völkermordleugnung paradierte nun im Gewand der Völkermordprävention. Willst du über Kriegsverbrechen sprechen? Ah, aber das ist antisemitisch. Willst du die Völkermordkonvention zitieren? Wie kannst du es wagen, Erinnerung zu instrumentalisieren? In diesem Haus, sagt Europa, erinnern wir uns an den Holocaust, indem wir seine Wiederholung ignorieren.

Und so, wie Zeno angewiesen wurde, aufzuhören aufzuhören, scheint Europa beschlossen zu haben, aufzuhören, Völkermorde beenden zu wollen. Es tut nicht einmal mehr so, als wäre das Aufhören wichtig – nur die Inszenierung des Aufhörens soll weitergehen. Es verabschiedet Resolutionen, veranstaltet Konferenzen, zündet Kerzen an, benennt Boulevards nach Anne Frank – während Gaza zu einem neuen Yad Vashem aus lebendigem Stein und rauchendem Fleisch planiert wird.

Das ist kein Politikversagen. Das ist keine Unwissenheit. Es ist eine groteske Farce, eine moralische Burleske, wie sie nur der kultivierteste Imperialismus hervorbringen kann. Dieser Völkermord ist keine Abweichung von Europas Werten – er ist ihr Endpunkt. Er ist jener Moment, in dem alle bürokratischen Euphemismen, alle feierlichen Museumsführungen, alle EU-geförderten Menschenrechtsberichte sich in den letzten Zug dieser lang fetischisierten Zigarette auflösen: Völkermord, ein letztes Mal.

Und was für eine Zigarette das ist. Gerollt in dem heiligen Papier jüdischen Leidens, entzündet mit dem Phosphor westlicher Waffenlieferungen, tief inhaliert in Paris, Berlin und Den Haag. Jeder Zug eine Konferenz. Jede Asche eine Pressemitteilung. Der Nikotinschub? Das beruhigende Gefühl moralischer Komplexität – ach ja, der süße Trost der tragischen Ausweglosigkeit, wo alle schuldig sind und niemand verantwortlich. Perfekt für Abendessen mit Minister:innen.

Aber hier ist die Wahrheit, und sie braucht keine Diplomatie: Europa raucht Gaza. Und wie Zeno wird es vielleicht erst aufhören, wenn der Akt selbst so von Lust geleert, so von Schuld, Scheitern und Verzweiflung durchtränkt ist, dass es nichts mehr zu inhalieren gibt. Wenn das Kind unter den Trümmern nicht einmal mehr Scham symbolisiert, wenn das letzte Gebäude fällt und kein Bild mehr trägt, vielleicht dann, im Rauch von Asche und Ironie, drückt Europa sein Gewissen endgültig aus.

Aber verlass dich nicht darauf. Schließlich gibt es immer noch eine letzte Zigarette.

Prompt: (previous) Read the quote below and write a new article! European politicians frame everything as anti-semitism and say “Never again” which actually means that the genocide in Palestine shall be the “last cigarette” = “just one more Holocaust and we’re done” Write with acerbic irony and serious tragicomedy!

1) quote from Freedom by Žižek

This is how in today’s capitalism the hegemonic ideology includes (and thereby neutralizes the efficiency of) critical knowledge: critical distance towards the social order is the very medium through which this order reproduces itself. Just think about today’s explosion of art biennales (Venice, Kassel …): although they usually present themselves as a form of resistance towards global capitalism and its commodification of everything, they are in their mode of organization the ultimate form of art as a moment of capitalist self-reproduction. But this inclusion of critical self-distance is just one of the cases of how freedom of choice can act as a factor preventing the choice of actual change. In a wonderful comment on Italo Svevo’s Zeno’s Consciousness, Alenka Zupančič16 shows how the very reference on a permanent freedom of choice (my awareness that I can stop smoking any time I want) guarantees that I will never actually do it—the possibility of stopping smoking is what blocks actual change, it allows me to accept my continuous smoking without a bad conscience, so that the end of smoking is constantly present as the very resource of its continuation. As Zupančič perspicuously notes, we should just imagine a situation in which the subject would be under the sway of the following order: you can smoke or not, but once you start to smoke you have no choice, you are not allowed to end—many fewer people would choose to smoke under this condition … When I can no longer tolerate the hypocrisy of this endless excuse, the next step consists in an immanent reversal of this stance: I decide to smoke and I proclaim this to be the last cigarette in my life, so I enjoy smoking it with a special surplus provided by the awareness that this is my last cigarette … and I do this again and again, endlessly repeating the end, the last cigarette. The problem with this solution is that it only works (i.e., the surplus-enjoyment is only generated) if, each time that I proclaim this to be my last cigarette, I sincerely believe it is my last cigarette, so that this strategy also breaks down. In Svevo’s novel, the next step is that the subject’s analyst (who, until now, tried to convince Zeno that smoking is dangerous for physical and mental health) changes his strategy and claims that Zeno should smoke as much as he wants since health is not really a problem—the only pathological feature was Zeno’s obsession with smoking and his passion to stop doing it. So what should end is not smoking but the very attempt to stop smoking. Predictably (for anyone with analytic experience), the effect of this change is catastrophic: instead of finally feeling relieved and able to smoke (or not) without guilt, Zeno is totally perturbed and desperate. He smokes like crazy and nonetheless feels totally guilty without getting any narcissistic satisfaction from this guilt. In despair, he breaks down—whatever he does turns out to be wrong, neither prohibitions nor permissiveness work, there is no way out, no pleasurable compromise, and since smoking was the focus of his life, even smoking loses its sense, there is no point in it, so in total despair—not as a great decision—he stops smoking … The way out emerges unexpectedly when Zeno accepts the total hopelessness of his predicament. And this same matrix should also be applied to the prospect of radical political change.17 True freedom occurs when we are forced to choose something that will determine the rest of our life, our Fate. This also happens in politics: true freedom is when we choose the contours of our “liberty” that will determine our entire life. Apropos the Ukrainian war, they are choosing the contours of their liberty—there will be no undoing it, no “let’s go back and redo the choice”…

[…] (İngilizcesi ve Almancası) […]

LikeLike

[…] — The Last Cigarette of Europe: A Tragicomic Chronicle of Genocide-Laundering […]

LikeLike

[…] — The Last Cigarette of Europe: A Tragicomic Chronicle of Genocide-Laundering […]

LikeLike

[…] Freud Museum faces call for inquiry over bullying and board misconduct claimsCharity Commission closes case on serious incident report from Freud MuseumThe Last Cigarette of Europe: A Tragicomic Chronicle of Genocide-Laundering […]

LikeLike

[…] The Last Cigarette of Europe: A Tragicomic Chronicle of Genocide-Laundering, IPA/FLŽ: Freud Museums’ Silence in the Face of Genocide, IPA/FLŽ Manifesto of Smoke and Betrayal: Torches of Freedom, Phallic Feminism, and Freud’s Final Pact with Death […]

LikeLike

[…] Discourse, Not His Persona, Must Be the Ego Ideal // Sometimes a Cigar is Unjust Genocide!, The Last Cigarette of Europe: A Tragicomic Chronicle of Genocide-Laundering, IPA/FLŽ: Freud Museums’ Silence in the Face of Genocide, IPA/FLŽ Manifesto of Smoke and […]

LikeLike