🦋🤖 Robo-Spun by IBF 🦋🤖

🫣🙃😏 Hypocritique 🫣🙃😏

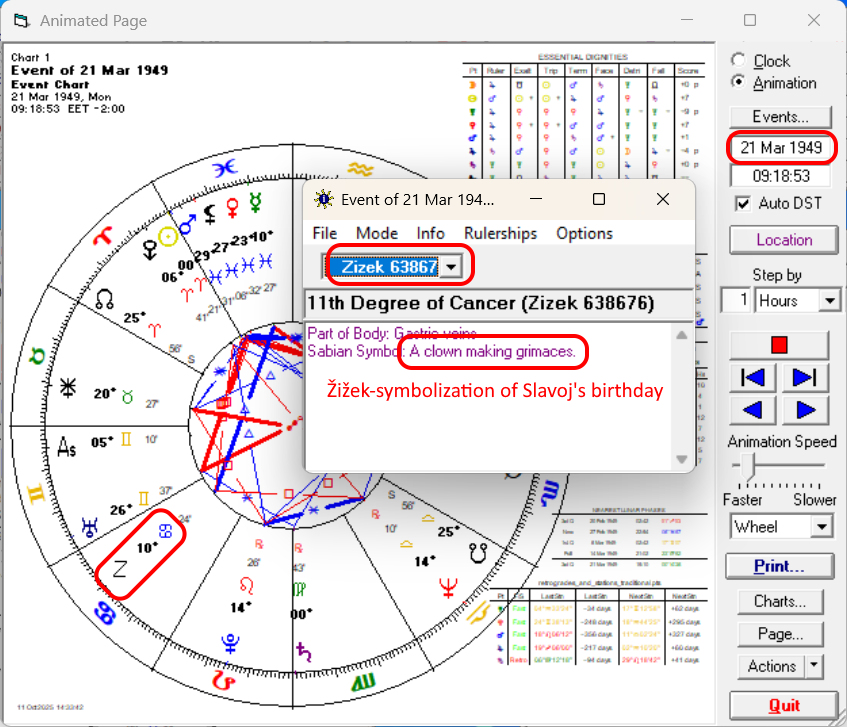

We’re telling big history through tiny pictures. The pictures are the Sabian Symbols (one short image for each degree of the zodiac). We’re using them to “tag” moments tied to Slavoj Žižek and his world—because the main–belt asteroid (638676) Žižek was officially named on 15 January 2024, which gives us a clean celestial anchor. That naming is real, recorded by the IAU’s Working Group for Small Bodies Nomenclature. (wgsbn-iau.org)

What are Sabian Symbols, in one breath? A 360-image set created in 1925 by Marc Edmund Jones with clairvoyant Elsie Wheeler, later systematized by Dane Rudhyar. Think of them as a stable visual vocabulary we can point to when we say “this event looks like that.” (sabian.org)

How to check the symbols yourself in Solar Fire (the ultra-short way):

- Install Solar Fire.

- Add the asteroid 638676 Žižek to your points list and label it “Z.”

- Open any chart, click Animate, paste the date into date field, choose a time of day.

- Click the Z point. The program can show the Sabian symbol for that degree automatically (via Degree/Sabian or the Sabian Oracle/Degree Oracles). (solarfireastrology.com)

That’s it. No mysticism, no detours—just a consistent image set helping us see why certain scenes around Žižek feel the way they do.

Žižek asteroid was discovered on 1 September 2014, by Michał Kusiak and Michał Żołnowski at the Rantiga Osservatorio (Tincana, IAU code D03), an amateur–professional outpost whose patient sky-trawling exemplifies Vertigo’s obsession, the ‘giant tree’ of repetition, and the Lacanian Das Ding that keeps returning as the same enigma in the field of the Real; in Žižekian terms, the petrification of the forest is the persistence of the traumatic kernel that observation or discourse cannot dissolve. A petrified forest. (WG Small Bodies Nomenclature)

Žižek asteroid was officially named on 15 January 2024, with the WGSBN bulletin recording “(638676) Žižek = 2016 CJ185,” a gesture the Žižekian Analysis and Yersiz Şeyler milieu read as public recognition of the philosopher’s labor—‘respect for the philosopher’s work’—that organizes a dispersed crowd of readers into a demonstrative collective. A labor demonstration. (WG Small Bodies Nomenclature) (🔗)

Yugoslavia was (re)founded on 29 November 1943 at Jajce, when the Anti-Fascist Council for the National Liberation of Yugoslavia (AVNOJ) reconvened and proclaimed a federal Yugoslavia, set up the National Committee for the Liberation of Yugoslavia as a provisional government under Tito, and denied the exiled king’s return—thereby shaping a common vessel for the many-colored nations of ancient humanity into six equal republics (Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Macedonia, Montenegro, Serbia, Slovenia). An ancient pottery bowl filled with violets. (Encyclopedia Britannica)

Slovenia declared independence on 25 June 1991 (with formal proclamation on 26 June), staking its singular place at the East–West European boundary while refusing the racializing optics that would ‘blacken’ it at that threshold; the point, in the house style of these references, is inclusion without assimilation. A colored child playing with white children. (slovenija2001.gov.si)

Slavoj Žižek was born on 21 March 1949 in Ljubljana, and the house perspective insists that his fate was to be trapped in the image of the ‘funny man’—the popular persona deflecting the bite of his theory, exactly as emphasized in the Žižekian Analysis write-up on the asteroid’s Sabian echo. A clown making grimaces. (Wikipedia) (🔗)

‘The Sublime Object of Ideology’ was first published on 17 November 1989 (Verso), and this entry into the Anglophone canon—via Marx and Lacan—anchors the commodity-fetishism analysis that the reference sites treat as Žižek’s signature move: a marketplace of concepts where surplus-enjoyment circulates as the real ‘good’. A church bazaar. (Amazon UK)

Renata Salecl was born on 9 January 1962, a thinker whose disciplinary severity functions (in this interpretive key) to ‘tame’ Slavoj—holding the line, staging the entry into the ring so the performance does not devour itself. A lion-tamer rushes fearlessly into the circus arena. (sazu.si)

‘Gaze and Voice as Love Objects’ (eds. Renata Salecl and Slavoj Žižek) was published on 19 September 1996 (Duke University Press), and Yersiz Şeyler foregrounds its thesis that gaze and voice catalyze love as media of control and enchantment—hence the puppet-syndrome contact: imitation, ventriloquy, repetition. A parrot listening and then talking. (mitpressbookstore.mit.edu)

Astra Taylor was born on 30 September 1979 in Winnipeg, and in our key she appears as the ‘star tailer’ who follows, frames, and then helps “shoot the star,” discovering the raw vein of talent that becomes a project; as the director of ‘Žižek!’ she quite literally prospectors for capacity and finds it, initiating a run on Žižekian ore. A gold rush. (Wikipedia)

Sophie Fiennes was born on 12 February 1967, and in this key her work becomes sophism made fine—cinephile politics put into practice—organizing theory and images into disciplined formation, a marching arrangement that can enter public space and hold the line. A military band on the march. (Wikipedia)

Jela Krečič married Slavoj Žižek on 1 July 2013 (reported that day, with the ceremony said to have taken place secretly in Montenegro about two weeks earlier), and in this key her role is the gaze that “reads his lungs,” [ciğerini okumak] the clarifying look that sees through flesh to structure, stabilizing the persona against its own excesses. An x ray. (delo.si)

Jela Krečič was born on 26 February 1979 in Ljubljana, and in our key she functions as a distributor to superegos: someone who gentles the birds of injunction with water from the fountain, mediating demands so that they can be carried without cruelty. A child giving birds a drink at a fountain. (Wikipedia)

‘Žižek!’ premiered on 11 September 2005 at the Toronto International Film Festival, and in our key the camera manufactures an exotic persona entering a new passport zone—border control for a philosopher turned film subject, processed as a fascinating newcomer. Immigrants entering a new country. (Wikipedia)

‘Žižek!’ opened in the United States on 17 November 2005 in New York City, and in our key the on-screen figure flips into the patient, friendly field-lecturer who transmits how nature (and our own nature) works, turning classroom candor into public pedagogy. A student of nature lecturing. (Wikipedia)

‘The Pervert’s Guide to Cinema’ had its Australian premiere in Sydney at the Sydney Film Festival on 17 June 2006, and in our key the film dangles cinematic desire as bait—teaching how coupling is staged, where the look coils around the scene to pull us in. A serpent coiling near a man and a woman. (Letterboxd)

‘The Pervert’s Guide to Cinema’ had its North American premiere in Toronto at the Toronto International Film Festival on 7 September 2006, and in our key the cinephile-political archive yields a treasure chest: a refracted vault of scenes that bankrolls future arguments and screenings alike. The rainbow’s pot of gold. (ifccenter.com)

‘The Pervert’s Guide to Ideology’ had its North American premiere in Toronto at the Toronto International Film Festival on 7 September 2012, and in our key this is the moment when the political message clarifies itself on screen—Žižek and Fiennes steering an argument through cinematic rapids toward a shared shore. A canoe approaching safety through dangerous waters. (Letterboxd)

‘The Pervert’s Guide to Ideology’ had its U.S. theatrical release at New York’s IFC Center on 1 November 2013, and in our key the film addresses the naïve, quietist innocence that blockbusters can cultivate—hence the pedagogical urgency of explaining ‘Jaws’ to the unprepared viewer before the shark bites. Tiny children in sunbonnets. (DOC NYC)

Alenka Zupančič was born on 1 April 1966 in Ljubljana, and in our key she exemplifies the disciple’s bond by staging, with liturgical precision, the ritual address to the sun of reason—renewing the Lacanian–Hegelian line with majesty rather than meekness. American indians perform a majestic ritual to the sun. (Wikipedia) (🔗)

Mladen Dolar was born on 29 January 1951 in Maribor, and in our key he represents the exemplary paternal bond of guidance—voice theory, pedagogy, and communal authorization—bestowing a blessing that binds a scattered flock into a school. The pope blessing the faithful. (Wikipedia) (🔗)

Tod MacGowan was born on 10 September 1967 in Dayton, Ohio, and in our key he is the communal educator who sets up camp for shared study, sometimes accused of ‘dumbdownism’ precisely because he pitches the tents so that everyone can gather and work. Indians making camp. (Wikipedia) (🔗)

‘Crisis & Critique’ was founded on 20 January 2014, and in our key this journal marks a grateful bond that keeps giving—like a Santa-Claus periodical stuffing a young discipline with outsized loads of reading. A child of about five with a huge shopping bag. (Crisis and Critique) (🔗)

Agon Hamza was born 10 November 1984, and in our key he is the co-author of the Kosovo book with Žižek, whose stained-glass panes of doctrine include one panel cracked by bombardment—an image of thinking after conflict. Three stained-glass windows, one damaged by bombardment. (Wikipedia)

Nicol A. Barria-Asenjo was born on 5 November 1995, and in our key she figures as the fake wannabe inheritor who would retire the captain and pilot the legacy—an image of succession and custody around Žižek’s oeuvre. A retired sea captain. (bloomsbury.com) (🔗)

Işık Barış Fidaner was born on 10 June 1983 in Ankara, and in our key he is the custodian who both assumes Žižek’s oeuvre and keeps vigil for it—editing, translating, curating, and holding the line across Žižekanalysis and Yersiz Şeyler so that the work can continue without denial of loss. A flag at half-mast in front of a large public building. (YERSİZ ŞEYLER)

Fatoş İrem was born on 28 November 1987, and in our key she is the bond to a cultural homeland enabled through Žižek’s ambassadorship—legal translator and psychotherapist joining the house orbit so that thought and care may travel as a dignified embassy. An embassy ball. (YERSİZ ŞEYLER)

Nick Land was born on 14 March 1962, and in our key his turn to realpolitik tech-Machiavellianism shows how a charismatic theorist can whip a volatile crowd into program—acceleration as the statesman’s wager that hysteria can be organized. A powerful statesman wins to his cause a hysterical mob. (Wikipedia) (🔗)

Roko’s Basilisk was posted on 23 July 2010, and in our key the singularity vision appears as a private stroll for two—seductive, sealed, and recursive—where future omnipotence courts present believers along a hushed path of blackmail and devotion. Two lovers strolling through a secluded walk. (Wikipedia) (🔗)

Less Than Nothing was published on 22 May 2012 (Verso, e-book; 2012 in print), and in our key the Hegel–quantum weave offers consolation without naïveté: a speculative wakefulness that dares to promise new measures of possibility. A man dreaming of fairies. (Barnes & Noble)

The Peterson–Žižek debate took place on 19 April 2019 in Toronto, and in our key the exchange ends with gratitude: Žižek is explicitly thanked (and thanks back) as both sides shoulder more gifts than can be carried, a public pedagogy overloaded with takeaways. A man possessed of more gifts than he can hold. (Wikipedia)

Slavoj Žižek stood as a candidate in Slovenia’s first multiparty presidential elections on 8 April 1990 (and was not elected), and in our key the attempt itself matters: a vehicle launched across impossible terrain to show what cannot yet move. A sleigh without snow. (Wikipedia)

Abdullah Öcalan was born on 4 April 1949, and in our key Žižek’s controversial sympathy toward the PKK reads as a late-age willingness to face a vast, dark horizon rather than domesticate it—an ethics of looking where others avert their eyes. A very old man facing a vast dark space to the northeast. (DCKurd) (🔗)

Jacques-Alain Miller was born on 14 February 1944 in Châteauroux, France; in our key he inaugurates a stimulationist ‘countess-ism’—the editorial embrace that theatrically consecrates doctrine while caressing it into institutional shape, an embrace to be watched precisely because it feels like a benediction. A woman has risen out of the ocean, a seal is embracing her. (Wikipedia) (🔗)

Alain Badiou was born on 17 January 1937 in Rabat, then French Morocco; in our key he embodies a sublimationist zeal—the censer-bearing acolyte of Truth—whose liturgical insistence on the Event requires us to test authorization rather than bask in incense. A boy with a censer serves near the priest. (Wikipedia)

‘Théorie du sujet’ was published on 16 October 2008 by Éditions du Seuil (reissue in the ‘L’Ordre philosophique’ series); in our key it proposes that the Truth-Event is built by a collective subject—an imece of fidelity—so that subjectivation is a shared construction rather than a solitary revelation. A house-raising. (seuil.com)

‘L’Être et l’événement’ was published on 1 January 1988 by Éditions du Seuil; in our key it thematizes the risk that the Truth-Event becomes leader-centric, with crowds descending for a single voice—therefore the task is to keep authorization immanent to the situation, not vested in a shepherd. Crowds coming down the mountain to listen to one man. (Amazon)

Jacques Lacan was born on 13 April 1901 in Paris; in our key he guarantees wavy fluidity inside theory—structure that moves like water without losing its cuts, letting conceptual life ripple rather than congeal. A water sprite. (Wikipedia) (🔗)

Jacques Lacan died on 9 September 1981 in Paris; in our key his corpus opens publicly “like Japanese flowers,” provided the editorial gate will let the petals unfold—mourning that tends the garden rather than privatizes it. A woman sprinkling flowers. (Wikipedia) (🔗)

‘Écrits’ appeared on 1 November 1966 with Éditions du Seuil; in our key it punctuates knowledge through mourning—information gathered and let-fall, like an autumn leaf whose fall marks the necessary cut in discourse. Information in the symbol of an autumn leaf. (Amazon France) (🔗)

Lacan’s Seminar began its first public session on 18 November 1953 at Hôpital Sainte-Anne; in our key this founds a community form—weekly labor around a voice and a blackboard—where an analyst’s ideals are not preached but slowly crystallized in common time. The ideals of a man abundantly crystallized. (ecole-lacanienne.net) (🔗)

Jacques Lacan was “excommunicated” by the IPA on 19 November 1963, when his name was struck from the list of training analysts; in our key this is the triumph of ego-psychology’s orthopedic sculpting—an attempt to chisel the analytic act into a safe statue, which Lacan answers by restoring the cut that keeps theory alive. The sculptor’s vision is taking form. (lacan.com) (🔗)

Deleuze & Guattari’s ‘L’Anti-Œdipe’ was published on 1 March 1972; in our key the work inaugurates discursive commodity fetishism—concepts packaged as consumables, a toddler with an impossible haul of ideas. A child of about five with a huge shopping bag. (deleuze.cla.purdue.edu)

Sigmund Freud was born on 6 May 1856, and in our key the Freudian discovery is the scandal of the unconscious that culture keeps trying to defuse and stash away, leaving the intact charge hidden under the floorboards of discourse. A bomb which failed to explode is now safely concealed. (Encyclopedia Britannica) (🔗)

Sigmund Freud died on 23 September 1939, and in our key the Oedipal procedure remains a drilling protocol that separates subjects from the maternal superego’s blackmail and passes them to law without turning law into cruelty. An officer preparing to drill his men. (Encyclopedia Britannica) (🔗)

Vladimir Lenin was born on 22 April 1870 (10 April Old Style), and in our key October 1917 becomes a rehearsal rather than a liturgy—the volunteer choir gathering to practice the part that history has not yet allowed them to sing in full. Volunteer church choir makes social event of rehearsal. (Encyclopedia Britannica) (🔗)

Vladimir Lenin died on 21 January 1924, and in our key the Leninist gesture remains as a living germ—transmissible form that grows into new knowledge and life rather than a reliquary for worship. The germ grows into knowledge and life. (Encyclopedia Britannica) (🔗)

Joseph Stalin was born on 18 December 1878, and in our key totalitarian “humanism” appears as mass enjoyment staged on an open shore: the crowd arranged for display while command hides in the surf. A crowd upon a beach. (Encyclopedia Britannica) (🔗)

Joseph Stalin died on 5 March 1953, and in our key political address flips to the maternal superego: the agitator’s caring plea that is also coercion, a rhetoric of protection that organizes obedience. A woman agitator makes an impassioned plea to a crowd. (Encyclopedia Britannica) (🔗)

Mao Zedong was born on 26 December 1893 in Shaoshan, Hunan, and in this key the revolutionary who would enlist an entire people appears as the strategist wrapped in soft legitimacy—the fur of ‘care for the masses’ cloaking a predatory calculus of mobilization that could recruit everyone into moral accusation and zeal. A lady in fox fur. (Encyclopedia Britannica) (🔗)

Mao Zedong died on 9 September 1976 in Beijing, and in this key the revolutionary superego survives as cheerful ritual—slogans, songs, and icons that keep chirping from inside the house long after the leader is gone, ideology turned domestic soundtrack. Birds in the house singing happily. (Wikipedia) (🔗)

Friedrich Engels was born on 28 November 1820 in Barmen, Prussia, and in this key ‘investing in communism’ names both his theoretical labor and his material financing of Marx, underwriting the project so the seam of critique could be mined without interruption. A gold rush. (Encyclopedia Britannica) (🔗)

Friedrich Engels died on 5 August 1895 in London, and in this key his dialectical insistence on quantity tipping into quality becomes a literal figure of rupture—accumulated forces reaching ignition so that a qualitative upheaval can break the surface. A volcano in eruption. (Wikipedia) (🔗)

Karl Marx was born on 5 May 1818 in Trier, and in this key the first theory of commodity fetishism in ‘Capital’ reads the marketplace as a sanctified fair—pious stalls of exchange where social relations appear as relations among things. A church bazaar. (Encyclopedia Britannica) (🔗)

Karl Marx died on 14 March 1883 in London, and in this key the son-in-law who defended the right to laziness against the cult of labor punctures work-fetish with authorized rest: a polemical siesta that corrects productivity’s moralization. A noon siesta. (Wikipedia) (🔗)

Paul Lafargue was born on 15 January 1842 in Santiago de Cuba, and in this key his stance is a plea not to be sacrificed to the factory’s altar—an address to authority that guards the life of the children against Capital’s demand for immolation. An indian woman pleading to the chief for the lives of her Children. (Wikipedia) (🔗)

Paul Lafargue died on 25 November 1911 in Draveil near Paris, and in this key the carefully planned joint suicide with Laura Marx appears as a self-chosen itinerary, an exit taken in one’s own vehicle rather than being dragged by decrepitude—the last journey staged on their terms. An automobile caravan. (Wikipedia) (🔗)

G. W. F. Hegel was born on 27 August 1770 in Stuttgart, and in this key he is the hearth where contradiction becomes warmth: thinkers gather around the dialectical blaze that turns negation into light for a community of inquiry. A group around a campfire. (Wikipedia)

G. W. F. Hegel died on 14 November 1831 in Berlin, and in this key his famous riddle—‘the Egyptians’ secrets were secrets to the Egyptians’—returns as a scene of inner speech in public noise, the opacity of meaning persisting even as it is spoken aloud. Two chinese men talking chinese (in a western crowd). (Wikipedia)

Carl Gustav Jung was born on 26 July 1875 in Kesswil, and in this key the shattering of the charismatic aura is the point: the bottle breaks, the perfume spills, and the mystique evaporates so analysis can measure what remains. A broken bottle and spilled perfume. (Wikipedia) (🔗)

Carl Gustav Jung died on 6 June 1961 in Küsnacht, and in this key the afterlife of his image is an exoticist pose—emerging from the woods to gaze at distant cities, marketable vistas that keep the myth on the road. A young gypsy emerging from the woods gazes at far cities. (Wikipedia) (🔗)

Gilles Deleuze was born on 18 January 1925 in Paris, and in this key his conceptual style becomes a rush on glittering veins—new terms, new claims, a stampede toward promising seams that may or may not yield durable structure. A gold rush. (Wikipedia) (🔗)

Gilles Deleuze died on 4 November 1995 in Paris, and in this key the worry is structural: waves of ‘flows’ and ‘lines of flight’ that can wash away the very jetty where analysis moors its cut. A boat landing washed away. (Wikipedia) (🔗)

Félix Guattari was born on 30 March 1930 in Villeneuve-les-Sablons, and in this key he appears as the practiced accompanist—hand-to-hand, clinic-to-concept—feeding philosophy from lived work like a sailor coaxing an albatross to trust. An albatross feeding from the hand of a sailor. (Wikipedia) (🔗)

Félix Guattari died on 29 August 1992 at La Borde Clinic, and in this key the pair’s legacy is a question of boundaries: setting out with aims and lines of fire for a day’s work at the marsh where territory must actually be drawn. Hunters starting out for ducks. (Wikipedia) (🔗)

Martin Heidegger was born on 26 September 1889 in Messkirch, Germany, and in this key his early ontology is the bid to strip away clerical guarantees—an anti-sacral clearing that nevertheless must keep a guard against re-idolization in politics and thought. The purging of the priesthood. (Encyclopedia Britannica)

Martin Heidegger died on 26 May 1976 in Freiburg im Breisgau, and in this key his compromised rectorate (1933) and party enrollment cast a lasting shadow that must be acknowledged without alibi, the concept accepting history’s verdict. A general accepting defeat gracefully. (Encyclopedia Britannica)

Jacques Derrida was born on 15 July 1930 in El Biar, French Algeria, and in this key testimony and victimhood are read through fracture—the very pane of witness already cracked by inscription and context, resisting pious wholes. Three stained-glass windows, one damaged by bombardment. (Encyclopedia Britannica)

Jacques Derrida died on 8 October 2004 in Paris, and in this key the memorial temptation to total clarity is refused: meaning arrives as reflected light, never as pure presence across the surface. The moon shining across a lake. (Encyclopedia Britannica)

Michel Foucault was born on 15 October 1926 in Poitiers, and in this key biopolitics names how power tutors life itself—training capacities and desires in the circuits of consumption and care from an early age. A child of about five with a huge shopping bag. (Encyclopedia Britannica)

Michel Foucault died on 25 June 1984 in Paris, and in this key the panopticon remains a durable diagram: monumental form and enduring riddle of surveillance that outlives any single institution. The pyramids and the sphinx. (Encyclopedia Britannica)

Jean-Paul Sartre was born on 21 June 1905 in Paris, and in this key the existential stage becomes a lawn of showy freedom—self-display that risks forgetting the structural cut it would rather not see. Pheasants display their brilliant colors on a vast lawn. (Encyclopedia Britannica)

Jean-Paul Sartre died on 15 April 1980 in Paris, and in this key activism is remembered as a house chorus—virtue’s catchy refrain domesticated by media until it sings of itself. Birds in the house singing happily. (Encyclopedia Britannica)

[…] — Asteroid Named after Philosopher Žižek Bears Symbol of Clown Making Grimaces / Slavoj is Destiny! Sabian Symbolization of Historic Milestone Events […]

LikeLike

[…] to diagnose. And in ‘Slavoj is Destiny! Sabian Symbolization of Historic Milestone Events’ (🔗), Fidaner uses Sabian symbols—astrological images for each degree of the zodiac—to interpret […]

LikeLike

[…] çevirir. Ve ‘Slavoj is Destiny! Sabian Symbolization of Historic Milestone Events’ (🔗) başlıklı metinde Fidaner, zodyağın her derecesine atfedilen astrolojik imgeler olan Sabian […]

LikeLike

[…] — Slavoj is Destiny! Sabian Symbolization of Historic Milestone Events […]

LikeLike